explorations in ethical design: meditations on sustainability

27.01.2020 Editorial

Photo credit: ico-D

As environmental and human suffering persist in new and unexpected ways, we see the role design is playing to shift attitudes and practices towards leading on renewable and regenerative alternatives. We've put together some of our thinking on the subject—a list of articles and videos about designing worldwide, perspectives on the biggest challenges we face and the designers and companies who are taking the making of meaningful, sustainable work into their own hands.

When we say that design needs to take the environment into consideration —one of the pillars of the Design Declaration—it is an easy thing to agree on, but a rather difficult thing to implement.

Ideally designers would be equipped to make all designs environmentally sustainable. The fact is, the tools we have to calculate environmental impact may be incomplete. The issue runs deeper and the implications can be extremely complex. When you try to evaluate something as broad as "environmental impact", you have to take into consideration: air, water, land pollution, cleanup costs, extraction impacts, energy consumption, direct and indirect effects, off-gassing, impacts on plant and animal life (and quality of life). The list is on-going. Because these factors impact each other in inter-connected and complex ways, the overall "calculation" is difficult to determine. How sustainable are our designs actually?

Photo credit: Omar Marques/Echoes Wire/Barcroft Media

There is also the ethical issue of whether the things we are designing need to exist? The life cycle embedded within each object is often longer than most people's lifetimes. Any object, piece of clothing, the design of a building and its interior, the first question every designer could ask themselves is: is all this necessary? A single event website and its server generates enormous heat and energy to produce; a paper brochure in which trees are chopped down, expends invisible energy in the production and distribution cycles; a free mug you receive at a conference—all of these have myriad effects on multiple species within distant ecosystems. What role are we playing in the creation of unnecessary "needs"? and is this ethical?

As a kind of Meditation on these questions, below are a series of articles from different sources that we have been looking at to try to understand where this issue stands today and how to position ourselves. We hope this will spark some thinking in you, as it did in us.

BIG COMPANIES, DESIGNERS + SUPPLIERS IN-TRANSITION: THE TEXTILE CONUNDRUM

Already A LOT of material exists. While recycling seems the obvious way out, many big companies have strict protocol about the origin of the recycled materials they use and the chemicals they might accidentally exude in the process of making new items.

Photo credit: IKEA

The research that is happening now with companies like IKEA, running tests on how best to use recycled material could help startups develop recycling technology for a market that demands that products be low waste and 'sustainably-sourced'.

Designer Afsana Ferdousi

Photo credit: Instagram

Meet the leading designers from Bangladesh: “67 of Bangladesh’s ready-made garment factories have the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) approval, an internationally recognised environmental and sustainable certificate from the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) [ ] with seven of these ranking among top 10 green factories in the world. 280 more factories in Bangladesh registered with the USGBC for LEED certification. However, putting those numbers into context, Bangladesh has a total of 4560 factories, with a total of around 4,000,000 employed. While there’s progress being made, there’s still a long road ahead."

Read some of the challenges big operations face:

- Before Ikea and H&M can use recycled fabrics, they have to figure out what’s in them. (Answer: lots of poison), Fast Company

- Meet the future of bangladesh's sustainable design talent, i-D

PROGRESS IN-VIEW: ETHICAL BIODESIGN

Some designers are addressing the textile conundrum, and having too much stuff by developing materials that react and act differently to their environments or form new kinds of relationships with bio-matter.

Designer Natsai Audrey Chieza

Photo credit: Toby Coulson

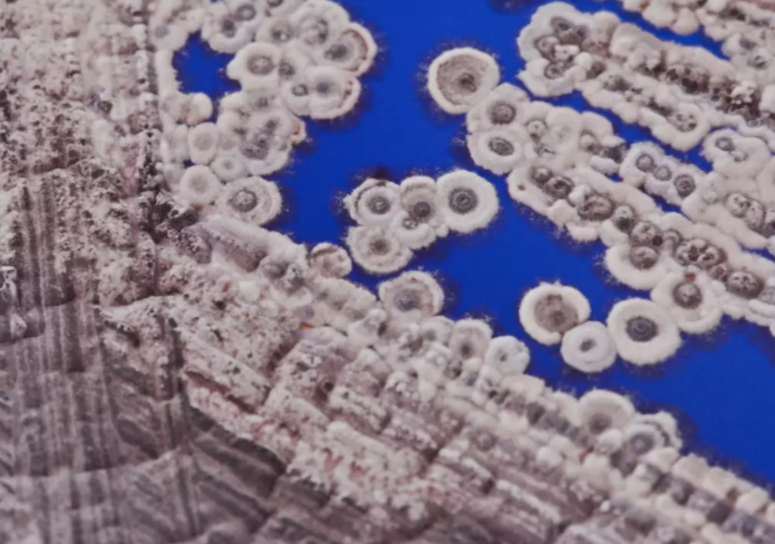

Designer Natsai Audrey Chieza (London) works at the intersection of biology and design, exploring how living organisms can make sustainable materials. Her creative partner and 'companion species' is a soil-dwelling bacterium that produces a pigmented compound which Chieza uses to dye fabric and garments in patterned hues of pink, purple and blue. Chieza hopes that biodesign can lead the way to more sustainable means of production, helping manufacturers to shift away from petroleum-based materials, divest from fossil fuels and reduce waste. With Faber Futures, she is also keen to develop an ethical framework for working with living organisms. “If we can engineer life, that means science has become a design space," she says.

Photo credit: The Rhizosphere Pigment Lab

Things you wear only once like a sequin dress? To avoid wasted resources, energy and labour fashion designers are creating fashion elements that dissolve and transform so that the garment has multiple usages.

Rachel Clowes, London-based embroidery and print designer

Photo credit: Andrew Woffinden

Have a look at these articles and studies:

- This designer uses living bacteria to dye clothes without water, Wired

- Biodegradable clothes may fix fashion's huge waste problem, Wired

RENEWABLE DESIGN: CHANGING HOW WE CONSUME

While some designers are making more innovative and sustainable products, other designers are working around issues of what we need/desire versus how much we should be consuming.

These articles are self-explanatory; about kids leading the way by adapting to consuming less and when they do, to use everyday products that are renewable. Fast Company has made a list of of these eco-friendly products for kids. They also talk about the accountability of phone companies and their yearly upgrades, and how-to deal with being reeled in to non-sustainable phone usage.

Kids want their schoolbags and lunchboxes, supplies, and clothes to be recyclable, refillable and to last!

Photo credit: Fast Company

Read the articles here:

- The Fast Company guide to eco-friendly back-to-school, Fast Company

- Dear Apple and Google: It’s time to stop releasing a new phone every year, Fast Company

The never-ending phone upgrades mean we are tempted buy a new phone every year (gulp)

Photo credit: Fast Company

REGENERATIVE: ON THE SCALE OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT WE NEED TO DO EVEN MORE

It's one thing to consume less, but how about repairing the damage we've already made? Some designers are suggesting a whole new paradigm based on accountability and "regeneration".

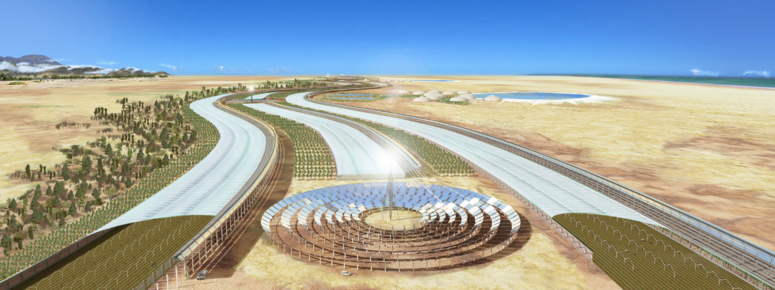

"We urgently need to look at what means to be regenerative" says Michael Pawlyn from Architects Declare, who believes working towards developing sustainable architecture—and a "no harm neutrality"—isn't enough. Architects need make buildings that will actually repair damage done to the environment and Pawlyn believes the solution is regenerative design. He describes this as "the development of restorative and renewable systems where output is always greater than input, beneficial for humans and other species." Instead of crediting buildings for achieving neutrality, regenerative systems such as biomimicry, which fosters a whole new relationship between buildings and nature, would lead the way by becoming compulsory.

Pawlyn is the founder of Exploration Architecture, known for biomimetic architecture like the Sahara Forest Project

Photo credit: Michael Pawlyn

The studio also uses 3D printing to mimic "resource efficient" structures found in nature, like crow skulls.

Photo credit: Kelly Hill

In line with this argument is Dutch architect Thomas Rau's proposal which works to develop a public database of materials for reuse in existing buildings. He asks, What if we stopped knocking buildings down and instead created a "material passport" for every building? Digital records of the specific characteristics and value of every material in a construction project would make it easier for different parts to be recovered, recycled and reused. The Dutch government has now introduced tax incentives for developers who register material passports for their buildings, and it is considering making it a mandatory requirement for all new projects, in line with its ambition to achieve a circular economy by 2050.

Read the articles here:

- "We fooled ourselves that sustainability was getting us where we needed to go" says Michael Pawlyn of Architects Declare, Dezeen

- The case for ... never demolishing another building, The Guardian

THE NEW BASELINE: SUSTAINABLE DESIGN AS MEANINGFUL WORK

The last Article is in fact a video and it is not actually about design at all. What UK philosopher Alain de Botton frames as "Work and Emotional Intelligence" sparks in us a kind of existential question about our profession and integrity as professionals and our desire for things as consumers.

We would posit that the most sustainable thing that we can do as Designers is reframe the question around desire. Sure, we could (and certainly should) work to reduce the impacts of the designs we produce. But maybe we should also be re-inventing ourselves as creators of meaning. Maybe people do not need more things? Maybe what they need is something else to fill their longings? De Botton argues that, for the past hundred years we have been trying to convince people that commercial products can solve their emotional needs. That their insecurities can be filled with luxury purses, that their loneliness can be remedied with social media and their hunger satiated with Uber eats. But this may be misleading. Maybe those needs can be more directly answered without producing physical things?

Botton's video sets-up the backdrop of a capitalist, consumer economy and what is driving people to change it:

We leave you with this thought. Maybe the future of design is to better understand what people really need to be happy? To repackage their true desires so that they can fulfil them without consuming. That true sustainability is creating less things while still filling people's needs.

relatedarticles

ICoD exclusive interview with kyle rath on design and AI

robert l. peters: guiding the future of design

ICoD interviews elizabeth (dori) tunstall on decolonising design

it may look good on instagram but you want to enjoy living in it