designing for access

21.06.2021 Editorial

Design can bring access to information, education, healthcare, well-being and even joy. While the assumption is that design makes lives better and more functional, making design ‘accessible’—able to be reached and used—is not a given. Providing access to certain material realities—to spaces, to knowledge and experiences—is not always fair and just. In fact, a fundamental part of the designer’s job is to understand how the interplay of social, economic, environmental, technological and geographic factors may grant or block fair access in certain contexts—and to find new ways to let more people ‘in’. Designing for access means consulting those who have the lived experiences encountering those spaces.

Design can bring access to information, education, healthcare, well-being and even joy. While the assumption is that design makes lives better and more functional, making design ‘accessible’—able to be reached and used—is not a given. Providing access to certain material realities—to spaces, to knowledge and experiences—is not always fair and just. In fact, a fundamental part of the designer’s job is to understand how the interplay of social, economic, environmental, technological and geographic factors may grant or block fair access in certain contexts—and to find new ways to let more people ‘in’. Designing for access means consulting those who have the lived experiences encountering those spaces.

Most designers strive for inclusivity, working closely with a well-targeted group of people or an individual. However, designing for everyone is impossible; one ‘universal experience’ is, more often than not, inadequate for most. This process of accounting for all the ways people interact and relate is core to the designer’s ethos and to the design methodology. In fact, not taking this responsibility seriously effectively means you are not a professional designer. In this feature, we address the ways in which designers control and deny access, and we outline new models that imagine a range possibilities to make professional design practices create works which are accessible, inclusive and collective.

Graphic designer Applied Design Works in collaboration with the nonprofit organisation Braille Institute to develop a "hyperlegible typeface" for the visually impaired community.

Graphic designer Applied Design Works in collaboration with the nonprofit organisation Braille Institute to develop a "hyperlegible typeface" for the visually impaired community.

DESIGN ACCESS IN CONTEXT — A HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

To understand how the conversation around accessibility came to be, it is necessary to understand how the language around accessibility evolved. Here is a brief a historical overview of some key terms in the field given by leading thinkers on the subject today. In some instances, these terms overlap or redefine the underlying issues.1

Accessibility is a general term referring to how well a design provides access; is able to be reached, entered or used by a user and is derived from an earlier term, barrier-free design. In the 60s and 70s, in accordance with civil rights legislation, architectural strategies were developed to design environments that supported the spatial needs of people with disabilities. At that time, some designers were also becoming more aware of differing needs for other populations, such as women and people of colour. The term barrier-free design reflected a concern over inaccessibly built environments (very common at the time, and even now!) and how these spaces made oppressed peoples less visible by containing or confining them. Barrier-free design attempted to address the social and systemic issues over who is acceptable to be seen and supported in society, and who must be hidden away. A decade later, as an outcome, architect Ray Lifchez’s groundbreaking text from 1987, Rethinking Architecture: Design Students and Physically Disabled People characterised how deeply, and differently, accessibility affected the everyday, lived experience:

Building forms reflect how a society feels about itself and the world it inhabits. … Valuable resources are given over to what is cherished—education, religion, commerce, family life, recreation—and tolerable symbols mask what is intolerable—illness, deviance, poverty, disability, old age. Although architects do not create these social categories, they play a key role in providing the physical framework in which the socially acceptable is celebrated and the unacceptable is confined and contained. Thus when any group that has been physically segregated or excluded protests its second-class status, its members are in effect challenging how architects practice their profession. (1987)

The Universal Design movement in the 80s went beyond barrier-free design hoping to produce built environments that would be accessible to a broad range of human variation. Universal design is defined as the design of an environment so that it might be accessed and used in the widest possible range of situations without the need for adaptation. Rooted in architecture and environmental design, this movement promoted building from the outset in a way that was accessible to as many people as possible and that would not require future retrofitting or alteration. As a way to broaden ideas around community and citizenship, the goal was to make the environment ‘functional for all people’, designing environments to be accessed and used in the widest possible range of situations without the need for adaptation. Key to universal design was erasing the ‘special needs’ category and normalising differences. The principles of universal design are focused on attributes of the end result, such as ‘simple and intuitive to use’ and ‘perceptible information.’ Three main ideas emerged from universal design practice:

Accessibility by design: Design that prioritises accessibility, referring to the methodology used to design a building or product that prioritises access, in addition to style and aesthetics.

Broad accessibility: Accessibility for the greatest number of people possible. Broad accessibility recognises the added value of design that benefits disabled people in providing benefits for non-disabled people.

Inclusive design is a trickier term to define as it refers to a method, but was born out of digital technologies in the 70s and 80s that made possible aids such as close captioning of film and video for people who are deaf and audio-recorded books for blind communities. Many consider inclusive design as synonymous with universal design coming from the notion of broad accessibility. However, Jutta Treviranus, Director and Founder of the Inclusive Design Research Centre and Inclusive Design Institute (founded in 1993 at the Ontario College of Art and Design in Canada) explained the difference between the two: Universal design is one-size-fits-all; inclusive design is one-size-fits-one.

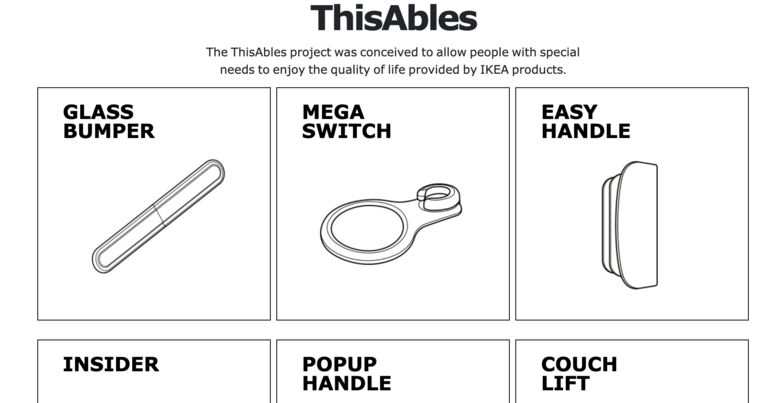

Co-created by IKEA designers in collaboration with disabled communications specialist Eldar Yusupov, ThisAbles (video) creates downloadable 3-D-printer templates for items like sofa lifts and oversized light switches that convert popular Ikea furnishings into accessible designs. ThisAbles is an example of being a recipient and creator of cool technology, but wasn’t necessarily credited as such.

In designer Susan Goltsman’s words, inclusive design “doesn’t mean you’re designing one thing for all people. You’re designing a diversity of ways to participate so that everyone has a sense of belonging." (Goltsman led her design projects with what she called the I-N-Gs; she would ask, “what I-N-G is most important to this environment?” Maybe it was running, digging, swinging, climbing, or sleeping. Whatever the I-N-G, the next question was always, “How many ways can human beings engage in that activity [in a particular environment] [with that product]?” Principal Director of Inclusive Design at Microsoft from 2014-2017 and author of Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design Kat Holmes makes an important distinction: “accessibility is an attribute, while inclusive design is a method. While practicing inclusive design should make a product more accessible, it’s not a process for meeting all accessibility standards." Holmes says the ideal is when accessibility and inclusive design work together:

“Inclusive design might not lead to universal designs. Universal designs might not involve the participation of excluded communities. Accessible solutions aren’t always designed to consider human diversity or emotional qualities like beauty or dignity. They simply need to provide access. Inclusive design, accessibility, and universal design are important for different reasons and have different strengths. Designers should be familiar with all three.”

— Kat Holmes

Universal Design describes the qualities of a final design and the nature of physical objects. Inclusive design, conversely, focuses on how a designer arrived at a solution. Accessible design refers to the outcome: who has access and who does not and in what ways.

Collective access design is a newer term that connects design to larger struggles for collective liberation and ecological survival. Sasha Costanza-Chock in her open source book Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need (2020) writes, "Keeping in mind that universalist design principles and practices can erase certain groups of people—specifically, those who are intersectionally disadvantaged or multiply burdened. Collective access design considers the multiple facets of identities, that people also characterise themselves in relation to race, class, gender, ethnicity, age, physical size and sexuality. This approach considers such interdependent complexity and aims to 'build a better world, a world where many worlds fit.'” The terms “collective access design” and “inclusive design” overlap, as shown in Holmes’ description of inclusive design: “An inclusive designer is someone, arguably anyone, who recognises and remedies mismatched interactions between people and their world. They seek out the expertise of people who navigate exclusionary designs. The expertise of excluded communities gives insight into a diversity of ways to participate in an experience.”

Hostile design is a newer term, referring to things designed on-purpose to make it difficult for certain sectors of society to not participate in positive experiences in daily life.

Hostile design refers to things designed on-purpose to make it difficult for certain sectors of society to not participate in positive experiences in daily life. (Photo credit to George Etheredge for New York Times.)

Hostile design refers to things designed on-purpose to make it difficult for certain sectors of society to not participate in positive experiences in daily life. (Photo credit to George Etheredge for New York Times.)

Becoming familiar with these terms is a start towards gaining multiple perspectives on what should be designed. Some questions to ask are: How does the design methodology process create a more accessible outcome, and for whom? What does the ‘in’ of ‘inclusive’ mean, anyway, and can we assume everyone wants to ‘belong’ in the same way? How do issues of inclusivity and universal design help to understand the designers responsibility to be accountable for the decisions they make, decisions that may withhold access from the less privileged, the less visible? How can the idea of designing for collective access shift thinking, research and decision-making in design—so that designers can take responsibility for the role they play in making better matched interactions between people and their world?

DESIGNING FOR ACCESS — THE TENSIONS

Access is not only about disability. For example, when designing electric cars, the designer must consider the needs of women, people who are colorblind, and any other specific needs or factors of the users. It is important to assume you do not know what certain groups want or need. When designing for a target market, it is the job of the designer to talk to all the users of the design. In other words, if you are designing for blind people, your design doesn't have to work for the sighted, but it does need to work for the entirety of the blind community, including blind women, blind people who may also be tall, blind BIPOC people, etc. This means considering the ways in which race, class, gender, ethnicity, age, physical size, sexuality, and physical and cognitive ability/neurodiversity intersect in relation to the built environment and space; things we use everyday; access to media, quality healthcare and education; a sustainable environment including land, water, and shelter; and joyful experience and well-being. It is the designer’s job to research and factor in what is needed in the designing process. Designers must always begin by remembering that the methodology of the designer is to gather information through consultation, and and to engage in the proper testing of their designs with their audience.

Expanding access is a core part of the designer’s professional responsibility. But what happens when a designer unconsciously or even consciously, does the opposite and causes access to be reduced or denied?

DENYING ACCESS

The designer who oversimplifies needs, not taking time to gather and consult with all the users they are testing for, can be implicated in denying access for users. Caroline Criado Perez documents how certain designs actually put women at risk—whether on the roads by using crash test dummies based on men’s bodies only, designing one-size-fits-all tech gadgets based on men’s dimensions, or designing safety equipment ill fits women’s smaller faces and exposing them to toxic chemicals.

Photo credit to Kellie French/The Guardian: The deadly truth about a world built for men – from stab vests to car crashes: ‘Serious injuries at work are increasing among women.’

Photo credit to Kellie French/The Guardian: The deadly truth about a world built for men – from stab vests to car crashes: ‘Serious injuries at work are increasing among women.’

Denying access can cause daily frustrations and even harm. Talli Osborne, disabled activist and speaker, argues that even when met, design standards for universal access fail in everyday built environments (mainly related to architectural decisions) such as streets, shopping malls and doctor’s offices, because architects have not worked hard enough to consult those who have the lived experiences encountering those spaces: “There are even many places I am completely unable to enter due to a large step or even a full flight of stairs. And that’s just getting in the door! Even if I get inside, there are usually so many barriers that I’m unable to get around comfortably or without possibly breaking something.”

Access is overtly denied through, ‘hostile design’: things designed on-purpose to make it difficult for certain sectors of society to not participate in positive experiences in daily life. This could include the designing of bars or studs installed on benches or in warm alcoves to prevent the homeless from resting or sleeping there. In all of these contemporary instances, it is clear that the ‘designer’ not only did not include the people using these objects and spaces, but are implicated in denying access to equal experience, health benefits and well-being.

In ways that are harder to pin down, designs can have a negative impact by causing a ripple-effect that goes beyond the intended users, especially in a world where we rely more and more on technology. In “Camera Obscura: beyond the lens of user-centered design,” the authors examine the failings of ‘user-centered’ UX design, writing, “There is a whole set of second-order experiences that we don’t actively design, but happen as a consequence of what we design. The blind spots include: obscuring the experiences of other participants who are not end-users, off-loading the frictional elements onto less visible or less privileged users, and preventing experimentation by only working with narrow metrics of what is considered to be a successful design."

However, this also means that there’s the potential for a great deal of positive change if designers work to understand that design is an interdependent network of effects and that access can be created simply by shifting how we look and what we look at.

ICoD’s STANCE ON ACCESSIBILITY

The International Council of Design contends that the minimum bar for 'good design' is that, beyond its narrowly-intended function, the outcome—the design—must consider the social, cultural, economic and environmental impact as integral parts of the solution. According to the Professional Code of Conduct for designers it is the designer’s professional responsibility to society uphold collective access.

Under the section “professional responsibility to society”, the Professional Code of Conduct for designers says this about accessibility:

Humans come in all shapes and sizes. Different genders have different attributes and physiologies. People have different needs and capacities as they grow and age. People have different physical and cognitive limitations and some have mobility challenges and needs. Certain groups have distinct needs (e.g., new immigrants, people with language barriers) and these needs should be considered in any design that is targeted to groups including them. One design cannot fit all. It is the responsibility of designers to consider how designs are carefully aligned to the demands of the users of each project.

CONCLUSION

A designer’s professional responsibility to humanity is paramount. Designers can do good, but they can also do harm. Everything a designer does is multiplied by a million. If a designer is controlling access, they must be aware that each minute decision can cause harm that spreads widely. To change this, we ask: How does your design take on the responsibility to build a better, more inclusive, fairer, collective world right where you are? Who are you not taking into consideration and what good or bad might this lead to? The next zeitgeist in design will be led by designers who take responsibility in designing for access—where the ethos is to design better connections between people and world they desire.

LEXICON

ABELISM Abelism centers productivity, and assumes everyone has great vision and hearing, and that bodies move fast and can adjust to any physical environment. Most of the world works according to these assumptions. Counter-ableist thinking challenges these assumptions through concepts such as ‘crip time’ and ‘going slow’.

ACCESSIBILITY A general term referring to how well a design provides access; enables a user to be able to reach, enter or a tool, object, or environment. The term is born out of an earlier term, “barrier-free design”.

ADDED VALUE Design that benefits disabled people also has benefits for nondisabled people.

BARRIER-FREE DESIGN In the 60s and 70s in accordance with civil rights legislation, architectural strategies were developed to design environments that supported the spatial needs of people with disabilities.The term barrier-free design reflected a concern over inaccessible built environments and how these spaces made oppressed peoples less visible by containing or confining them. Barrier-free design attempted to address the social and systemic issues—over who is acceptable to be seen and supported in society, and who must be hidden away.

ACCESSIBILITY BY DESIGN Design that prioritises accessibility; it refers to the methodology used to design a building or product that prioritises access, in addition to style and aesthetics.

BROAD ACCESSIBILITY Accessibility for the greatest number of people possible.

COLLECTIVE ACCESS DESIGN

This is a newer term that connects design to larger struggles for collective liberation and ecological survival. Collective access design is part of the disability justice framework and considers the multiple facets of identities, that people also characterise themselves in relation to race, class, gender, ethnicity, age, physical size and sexuality. This approach to design considers such interdependent complexity in its expanded methodology.

HOSTILE DESIGN Things designed on-purpose to make it difficult for certain sectors of society to not participate in positive experiences in daily life.

INCLUSIVE DESIGN Many consider inclusive design as synonymous with universal design, coming from the notion of broad accessibility. Author of Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design Kat Holmes makes an important distinction: “accessibility is an attribute, while inclusive design is a method. While practicing inclusive design should make a product more accessible, it’s not a process for meeting all accessibility standards. Holmes says the ideal is reached when accessibility and inclusive design work together. Universal design describes the qualities of a final design, the nature of physical objects. Inclusive design, conversely, focuses on how a designer arrived at the given design. Accessible design refers to the outcome: who has access and who does not, and in what ways.

UNIVERSAL DESIGN (UD) The Universal Design (UD) movement in the 80s went beyond barrier-free design hoping to produce built environments that would be accessible to a broad range of human variation. Universal Design is defined as the design of an environment so that it might be accessed and used in the widest possible range of situations without the need for adaptation. Rooted in architecture and environmental design, this movement promoted building from the outset, in a way that was accessible to as many people as possible and that would not require future retrofitting or alteration. The principles of universal design are focused on attributes of the end result, such as ‘simple and intuitive to use’ and ‘perceptible information.’ Three main ideas emerged from universal design practice.

FURTHER READING

Who am I designing for, and what is the context? Who should I ask to advise on this design? There many leading thinkers on accessibility and design models for professional design practices:

Aimi Hamraie, Associate professor of Medicine, Health, & Society and American Studies and director of the Critical Design Lab at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, TN who provides an in-depth study of the history of accessibilty in design as well as Jutta Treviranus, Director and Founder of the Inclusive Design Research Centre and Inclusive Design Institute (founded in 1993 at the Ontario College of Art and Design in Canada).

Designer Susan Goltsman helped to establish ADA guidelines for outdoor environments and is co-author of Play for All Guidelines, and The Accessibility Checklist.

Kat Holmes is the Principal Director of Inclusive Design at Microsoft from 2014-2017 and author of Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design. See this Fast Company article for more.

Anthropologist Dr. Dori Tunstall who works at the intersections of critical theory, culture, and design (video) is interested in human values and design as a manifestation of those values. Tunstall observes that design translates values into tangible experiences and asks others to consider what their values are.

Methods can be commonsense and even radical in their approach. Scholar, participatory designer, and activist Sasha Costanza-Chock, author of the (open source) book Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need (2020) argues that, to build the worlds we need, media, design and social movements need to work together. Read also their article Nothing About Us Without Us.

Researchers of Universal Design: A Step toward Successful Aging defines ageing successfully as (1) a low probability of disease and disease-related disability; (2) a high level of physical and cognitive functioning; and (3) an active engagement in life. Changing the built environment in the following ways greatly reduces feelings of stigmatisation and promotes ease of movement, general physical access, ability to understand and communicate, reduces fatigue and makes for better engagement in social activities. Some of these universal design options include: Doors that automatically open; Automated teller machines' buttons far enough apart to be pressed accurately; Providing furniture assembly instructions in a series of clear illustrations instead of text; Computer software that relays information visually through text and pictures, and audibly through speakers; Hallways that return to common areas rather than stop in dead ends; Bottle caps that are easy to grip and require only a small range of motion to open; Wall mounted components (i.e., toilet paper) that are visible, easy to reach, and easy for all hand sizes to use.

Senongo Akpem Cross-culture Design / UX designer, illustrator and the founder of Pixel Fable, a collection of interactive Afrofuturist stories, and also a vice president of design at Nava He is the author of Cross-Cultural Design from A Book Apart (article) which explores a clear methodology and techniques for designing across cultures and languages.

Intergenerational and youth-centered with a focus on education, the Creative Reaction Lab works to redesign educational curriculum to support racial equity, social healing and youth leadership by having Black, Latinx and Indigenous youth lead the shift.

Designer Deanna Van Buren with Designing Justice + Designing Spaces, an Oakland-based architecture and real estate development non-profit works to end mass incarceration by building infrastructure that addresses its root causes: poverty, racism, unequal access to resources, and the criminal justice system itself. They work in courthouses, prisons, and jails—to create spaces and buildings for restorative justice, community building, and housing for people coming out of incarceration.

Eyal Weizman founding director of Forensic Architecture and Professor of Spatial and Visual Cultures at Goldsmiths, University of London has created a multidisciplinary research group that uses architectural techniques and technologies to investigate cases of state violence and violations of human rights around the world.

Ahmed Ansari, Industry Assistant Professor at New York University at the Integrated Digital Media programme in the department of Technology, Culture & Society calls for a “delinking from the present world-system” to make space for many different ways of thinking, being, and designing, derived from different artifices and worldviews, aimed at addressing many different needs and desires...” While delinking is not an options for all designers—what can be taken from this is the necessity of looking through the cultural lens everytime you sit down to a project.

Other initiatives speak to a new movement to make objects and technology more inclusive for a variable disabled market such as Nike no-hands shoes, Lego braille for the blind, and a "hyperlegible typeface" for the visually impaired community. The body movement-recognition system developed by Valentin Gong, Xiaohui Wang and Lan Xiao, three designers from the Royal College of Art and Imperial College London, enables amputees and people with disabilities to use gesture-controlled smart devices more effectively. Huawei has developed an app that uses artificial intelligence to allow the visually impaired to "see" the emotion on the face of someone they are talking to by translating it into sound speak to a new movement to make objects and technology more inclusive for a variable disabled market.

The problematics and importance of bringing disabled people in to share their perspective on what the design needs to be can be seen in the example of the modular IKEA furnishings called ThisAbles (video). ThisAbles creates downloadable 3-D-printer templates for items like sofa lifts and oversized light switches that convert popular Ikea furnishings into accessible designs. Co-created by IKEA designers in collaboration with disabled communications specialist Eldar Yusupov, ThisAbles is an example of being a user and creator of cool technology, but wasn’t necessarily credited as such.

Scope=Equality for Disabled People has created a Social Disability Model, a reminder that the design issue is not with the user, but rather with how badly the thing is because of its design. In their work to change attitudes about disabilities, they counter medical models that insist on assimilating or ‘fixing’ the disabled person to ‘catch’ up with normative ableist society, offering instead a social-ethical model for day-to-day interactions.

By shifting lived experience and how we think about each other, ethical design will follow suit. Countering ableist notions, The Big Life Fix, a reality TV program that aired on BBC2 in August 2018, was a series that brought together leading designers to create new inventions that would improve the quality of life for people with specific needs. In addition to giving a more accurate portrayal of what designers and engineers actually do, the programme became a success for how it moved the conversation around disability away from senses of either pity or awe, and towards seeing disabled people as individuals who just want to do things, but need a bit more consideration from society to allow that. Working on ‘crip time’ and generally, ‘going slow’ is also counter-abelist thinking.

In terms of resources for professional designers, an ethical design strategy checklist was developed by UX designers with the goal of shifting the lens on access (mainly by going beyond user-centered design). This checklist helps designers “examine [their] values and principles, reveal invisible participants, understand the interplay of incentives in [their] network, and expose potential impact of [their] product or service.” [Step one is to uncover the exploits which means counteracting the patterns and mitigating factors in design that works with “misuse, abuse and bad actors” in an ecosystem and instead, re-thinking it. The next step is to consider alternate outcomes that might occur: identifying other design outcomes that might happen showing paths for both innovation and risk. The next step is to use systems mapping: identifying all the actors in the network, the flows, the incentives and disincentives, and the risks. Next is to design for excluded users. This means consciously designing beyond your usual expected user group. Finally, Lloyd gives the final step: employ ethics-oriented competitive research which means examining other products similar to yours to find out what you find to be ethical, and what you want to do better or differently.

Queer, disabled femme writer Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha has created a toolkit for building/designing resilient, sustainable communities in their book called Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice (2018) where “no one is left behind”. They remind us that oneday, we will all require a revised idea about our own ability to access things. For Piepzna-Samariasinha, ‘collective access’ is first and foremost about care, defined “not as a chore but as a collective responsibility and pleasure” where spaces are created by and for sick and disabled queer people of colour. ‘So much of the time,’ writes Piepzna-Samarasinha, ‘the furthest able-bodied activists get, when they remember disability at all, is the “inclusion model” where they want to bring us into the movement. This assumes that disability is somewhere far away, not already in our lives and movements. The disability justice framework flips this by centering access and disability in the everyday work that is already being done.’

NOTES

1 Some of the leading thinkers on accessibility in design include Aimi Hamraie, Associate professor of Medicine, Health, & Society and American Studies and director of the Critical Design Lab at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, TN—from whom we acknowledge borrowing the phrase “designing for collective access” (for this article), and who provides an in-depth study of this history. Also Jutta Treviranus, Director and Founder of the Inclusive Design Research Centre and Inclusive Design Institute (founded in 1993 at the Ontario College of Art and Design in Canada), designer Susan Goltsman who helped to establish ADA guidelines for outdoor environments and is co-author of 'Play for All Guidelines', and 'The Accessibility Checklist', Kat Holmes, Principal Director of Inclusive Design at Microsoft from 2014-2017 and author of Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design and Sasha Costanza-Chock author of the (open source) book Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need (2020). Here we’ve attempted to summarise some of the viewpoints.

Universal Design: A Step toward Successful Ageing, Journal of Ageing Research

Kelly Carr, 1 Patricia L. Weir, 1 Dory Azar, 2 and Nadia R. Azar 1 ,*

relatedarticles

ICoD exclusive interview with kyle rath on design and AI

robert l. peters: guiding the future of design

ICoD interviews elizabeth (dori) tunstall on decolonising design