professional designers do not participate in spec competitions

14.03.2022 Professional Practice

Speculative design award competitions would not thrive without the designers that submit work to them. This is why designers should choose to take a stance and not support this practice and why design organisations should play a role in supporting them.

Often we are asked by Members to support them in speaking out against crowd-sourced design competitions— otherwise known as 'spec competitions' or sometimes, ‘design challenges.' We sometimes do this publicly but often this is a process that takes place behind the scenes. This is a particular form of competition that the Council deems to be both unjust to designers and unprofessional for designers to participate in.

The Adobe X Billie Eilish 'Make the Merch' Competition drew a lot of criticism from designers and design organisations for asking designers to work for free to create tour merchandise to benefit a giant corporation and a very successful singer.

The Adobe X Billie Eilish 'Make the Merch' Competition drew a lot of criticism from designers and design organisations for asking designers to work for free to create tour merchandise to benefit a giant corporation and a very successful singer.

A key problem with these types of contests is that, to function, they require a large number of designers to submit work. Without such vast participation by designers, the practice would fail to generate the publicity the organisers seek. While the Council and its Members continue to advocate against crowd-sourced design competitions, as long as designers continue to work unpaid in this and other forums, we are working at cross-purposes with each other. Furthermore, encouraging design students to participate in competitions as part of their training and course-loads only normalises this behaviour.

For the message: "design is professional work that must be paid for professionally" to take hold, the industry as a whole must be consistent in upholding this message and supporting professional conduct. It goes without saying that professional associations and promotional bodies should not support or participate in these contests. Educational institutions can offer this support through the teaching of professional practice and ethics in their schools and educating their students to refuse to submit work to crowd-sourced or ‘spec’ design competitions. But designers must do their part. They are the ones who, through their daily actions, define industry norms.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

Why are design contests unethical?

We are not saying that all design contests are unethical. There is a distinction between competitions rewarding existing work (which we encourage, as long as they adhere to Best Practices) and what we are calling 'spec competitions,' that is, competitions that are asking designers to create new work. The latter is deemed ‘spec' (speculative work) because they ask designers to contribute professional services without compensation. It is speculative because one designer out of perhaps thousands, will be "paid" with prize money. The rest, despite the hours and expertise they contribute, have "gambled" and lost.

But competitions like those are common in architecture and other disciplines, how is this different?

They are different for several reasons. First, because architects do not submit finished projects. A 'sketch' in architecture might be a much more detailed design but architects are asked to submit a concept not the finished plans. In a logo competition, the contests do not ask for an idea for a logo, they ask for a logo. Secondly, those pitching are not individuals. Architecture studios budget for pitching costs. The industry is structured around this way of working and the costs of the concept design are already included in the pricing structures of the work.

But if I choose to gamble for the possibility of gaining recognition and free promotion, that is my business?

This is a classic tragedy of the commons issue. If every individual did what benefited them, at the loss of everyone else, then everyone loses. Because designers accept to work uncompensated all the time, design is perceived to be something that is not worth paying for. This is one of the contributing factors to why professional associations and other design bodies struggle so hard to prove the value of design. Once professional designers learn that their behaviour—and that of every other designer—is what sets the bar for how design, design services and designers are perceived, they will stop treating their work as something they can give away. If lawyers chose to work for "exposure" (and for free!) they would have the same legitimacy issues.

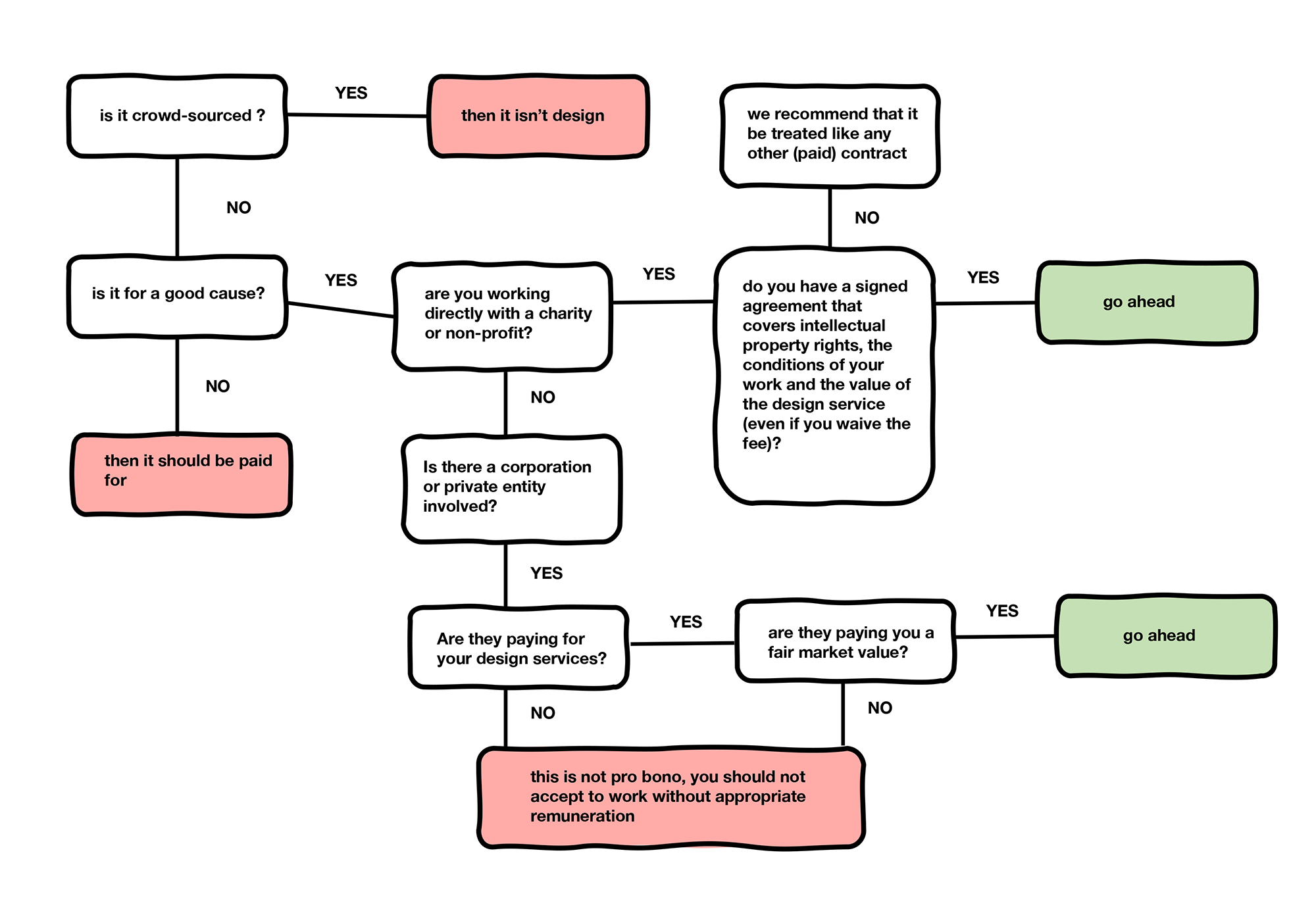

What if it is for a good cause?

The Council actively encourages Pro Bono work. But this is not Pro Bono design work. Because it is not design work. Just because it is a good cause (and you should ask yourself if it legitimately is), does not mean that it is ethical or advisable that it be crowd-sourced. The competition format does not work for this. First, because this structure forces most designers to work for nothing (not even a good cause). And secondly, because crowd-sourcing and design methodology do not work concurrently. For a proper design process to take place, the designer must work with the client, users and other stakeholders. This is circumvented when a contest announces a 'brief' and a multitude of designers respond as best they can with the information they have. Because the work is likely to be unpaid, unseen and unused, this often leads designers to try to take shortcuts like copying or taking the first easy idea. The resulting work is both wasteful—especially when multiplied by all the designers who are working on submissions—and usually not good.

It is advisable instead for designers to work directly with the recipients of Pro Bono work as they would with any client. The precise working relationship between the designer and the recipient should be carefully determined, defined and described in an agreement. The conditions of undertaking Pro Bono work, including ownership of rights and expenses, should be adhered to strictly and the value of the design services rendered should be communicated clearly to the Pro Bono recipient, even if no money changes hands.

Design 'challenges' are OK though, right?

Design challenges serve various purposes. Sometimes designers, illustrators and other creatives keep their skills fresh by doing work for their personal growth. These challenges are community- and skills- building exercises that are for the pure enjoyment of the exercise. They give designers and illustrators a chance try new techniques, explore topics that interest them personally and share with their peers. No one profits from this materially. Another format of challenge is when social organisations need help solving a concrete problem. For instance, to create way-finding quickly and at a low cost when a refugee crisis brings large numbers of people into a city where they do not speak the language. Or portable ways to purify water without chemicals for transient communities. These are actual problems that need solving. Those who will benefit from the challenge are legitimately in need.

What's the difference between a legitimate 'design challenge' and a spec competition?

There are a few red flags one should look for. The point of a legitimate design challenge is to create a solution, or several viable solutions. The incentive for designers to participate is not the possibility of payment, but rather the knowledge that they are contributing to society or that they are gaining in some way personally, generally by learning something. If designers would not participate were it not for the 'prize,' it is probably a spec competition. If there is a corporation or private entity involved, profiting off the publicity, it is very likely a spec competition since design challenges are generally designer-to-designer or designer-to-INGO. If the problem being solved is commercial in nature, then it is most certainly is a spec competition.

What if the profits are being donated to a charity?

Concretely, the company running the competition is using the budgets they are saving by not paying for design services to generate value. The designs they received (uncompensated) are commercialised, generating income. They then use the income they generated (off the back of designers who contributed their work unremunerated, remember) to then donate the profits they have made — because it is usually the profits, not the revenue — to a charity. Taking the credit for themselves, they then use the promotional value of the donation to build their brand. This is not only disingenuous but exploitative.

LEXICON

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS: the intangible rights to created works, such as written works, works of art, designs, images and symbols, musical works, filmed works, software, inventions, and other works. In most countries, intellectual property rights cover four broad categories of rights: copyrights, patents, trademarks, and trade secrets. Intellectual property rights are exclusive rights, granted to ‘rightsholders’ (creators or authors, inventors, and businesses). By enabling creators to monetise and profit from their work, intellectual property rights encourage the development of creative expression, new technologies, and new inventions, resulting in economic growth.

PRO BONO: it is widely misunderstood that the Latin ‘pro bono’ means ‘for free’. In fact, the term means ‘for good.’ To work to advance a deserving cause is encouraged. However, the precise working relationship between the designer and the recipient should be carefully determined, defined and described in an agreement. The conditions of unremunerated work, including ownership of rights, should be adhered to strictly. The value of the design services rendered should be communicated clearly to the pro bono recipient.

SPECULATIVE PRACTICE: speculative practices (also called ‘spec work’ or ‘free pitching’) are defined as: design work (including documented consultation), created by professional designers and organisations, provided for free or for a nominal fee, often in competition with peers and often as a means to solicit new business. The Council recommends that all professional designers avoid engaging in such practices.

relatedarticles

the 'pro bono' primer

VIDEO: why professional designers should not participate in spec competitions

resources for displaced designers