DESIGN AND THE ECONOMY

21.01.2009 Features

This week's Feature is the translation of a speech presented by Ruth Klotzel (S?o Paulo, Brazil) to the first Bienal Iberoamericana de Dise?o held in Madrid, Spain in November 2008. It is reprinted with permission.

This meeting of Latin American countries is very significant, not only in the sense of knowing, discussing and disseminating design from our region, but also to see how it has changed the focus of the economy in recent times, giving space to the search for alternative solutions in different cultural contexts, such as developing countries.

The topic I want to focus on - design and the economy - refers to new paradigms that have emerged, looking for alternatives to our bleak forecast for the future.

Our model of development, modeled on the rampant growth of production and consumption, has caused catastrophic results: it led to environmental degradation and depletion of natural resources, social imbalances and the economic crisis we are witnessing today.

Brazil, as well as some other Latin American countries, has grown and modernised, mainly since the 1970s, reaching today a respectable presence on the world stage. But the cake has not been divided and our discussion has revolved around the assessment of GDP growth.

The distortions and misfortunes of this culture of super productivity - hysterical consumption in a world where people still die from hunger - made us wake up and question what kind of development we want. We know that to truly flourish as a society depends on our policy options.

Design is one of the important players in this context. Therefore, within the profession, self-reflection on what we are doing, what space we have, how we work, what we stand for and what is our desired path is essential.

On the conceptual level, it is not by coincidence that the new movements like Slow Tech (Fran?ois Bernard) are appearing now, suggesting a slower pace for a better quality of life. Bernard proposes a dematerialised world with less focus on technology, revisiting nature and a simplified way of life, distanced from our culture of the disposable.

Metropuritanos - a term used to describe a new trend that preaches organic production, consumption, ethical and fair trade – is a reaction to the practice of modern consumption and its links to mass destruction.

Product development in a sustainability context embraces simplicity, economy, variety and quantity of materials, durability, and optimisation of manufacturing processes. In other words, simplification means reduced production costs, prices, consumption and profitability, and constitutes a paradox in relation to an economy based on financial gain, increased production and consumption.

It is a discussion that summarises the search for an alternative energy matrix, which in itself is a vast and complex issue, that I do not intend to pursue here.

In recent years, I have had the opportunity to participate in conferences and meetings and to get to know designers from many different cultures, and I have noticed how the so-called developing countries, which have a very strong local culture, have been the focus of interest in schools, industry in general, fashion, and cultural production.

But if there is interest in culture, knowledge and approaches that were once considered alternative, there is still exploitation and inequality, so that products are designed in large centres, production is done on the periphery, and the product brought back to market in these same large centres.

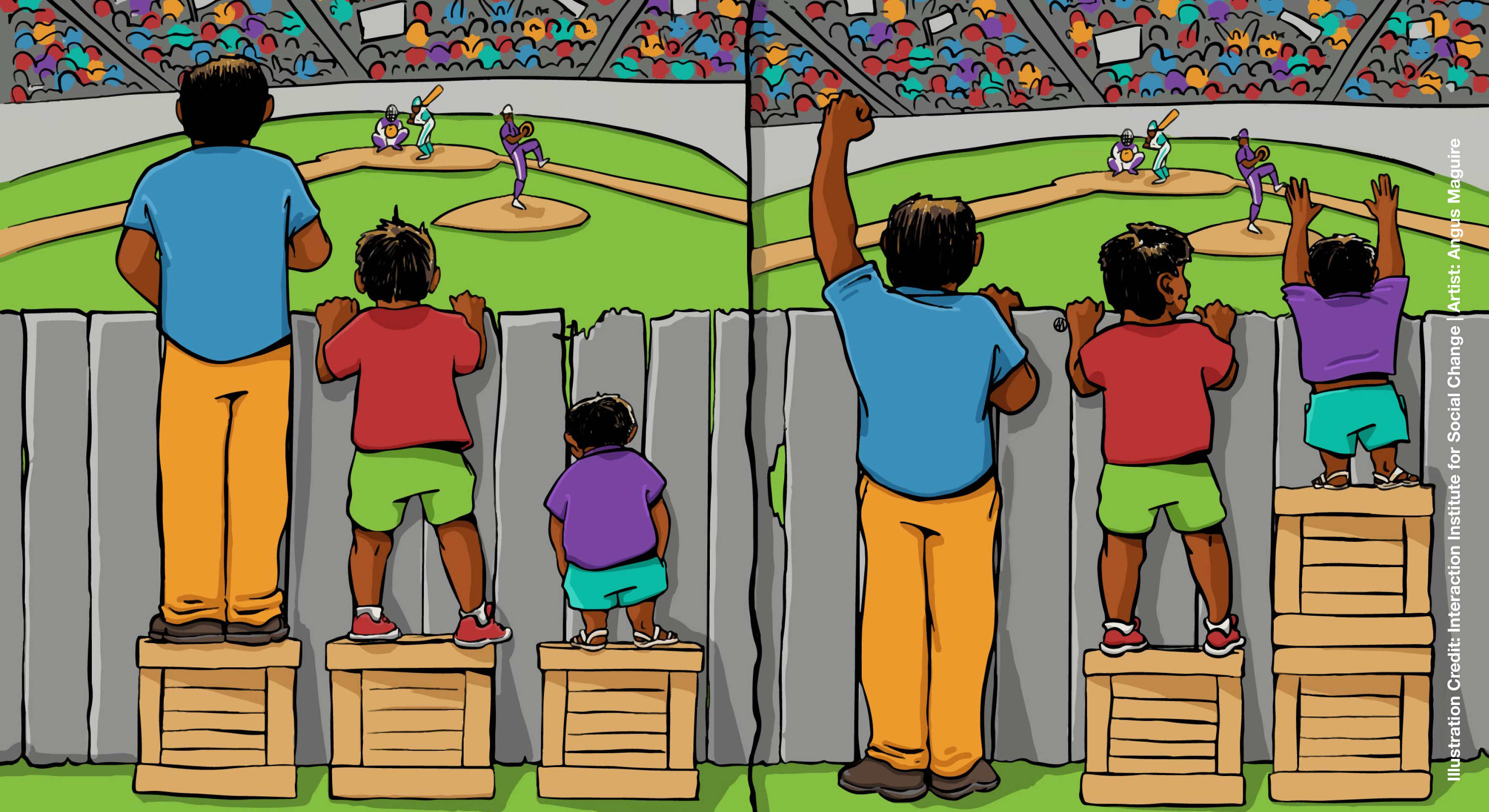

Another aspect that I want to mention is about design and democracy. Gui Bonsieppe said that democracy is, to neoliberalism, the dominance of the market as a unique and almost sacred institution that governs all relations between societies. He asks how we can recover the notion of democracy in the sense of civic participation, opening up space for self-determination. Put another way, the nature of democracy goes far beyond the right to vote, in the same way that freedom is more than a choice between hundreds of different models of mobile phones.

In BonsieppeÂ’s view, design must also come from the periphery, and not be done for the periphery as a result of a kind of benevolent paternalistic attitude. Design must be based on local practice, since some problems can only be solved in the local context.

We have many challenges but we also have a potential way forward: we can formulate new equations seeking healthier development models. This is not a trivial discussion in some parts of Latin America, not only in terms of design but also the development model as a whole.

At the heart of this discussion, design policy should establish broad parameters, because design is the link between the material and immaterial, and is the central link between the worlds of art and commerce. It is committed to improving form and function and has a great potential when it comes to improving the quality of life.

According to a recent report from United Nations Conference on Trade and Development in partnership with the South-South Cooperation Special Unit, design is one of the four core strategic activities of the so-called creative economy.

The main difference of the economy based on creativity is that it promotes sustainable and humane development, and not just economic growth.

according to Lala Deheinzelin, when we work with creativity and culture, we act simultaneously in four dimensions: economic, social, environmental and symbolic. That leads to an unprecedented exchange of currencies: economic investment, for example, can generate social return on investment; environmental investment can generate a symbolic return on investment, and so on.

An economy based on creativity is strategic, not only for the creative business, but also for those who gain competitiveness through what we call the "culturalisation of business" adding value through intangibles and cultural attributes.

According to the UNESCO Convention on Cultural Diversity, cultural goods are unique and distinct, carrying a high symbolic worth, intangible value, rich history accumulated over centuries, resulting from the flow, interactions and learning that occurred along the many planes of life.

Design has the ability to contribute to the unique experience of living, building situations and objects that surprise, thrill and function, communicate, materialise experiences and knowledge that are the heritage of a people. This is when democracy becomes accessible and, more importantly, when there is a spirit and a collective need.

In conclusion, when I was watching television last week, I saw the Brazilian economist Eduardo Gianetti commenting that the institutional world was far behind the real world, because globalisation requires rethinking and reformulating multilateralism.

This brought me back to a circular phrase, which I adopted several years ago, when I discovered it in the floor tile around the clock tower at the University of S?o Paulo. It was written by the of former rector and jurist Miguel Reale: "In the world of culture, the center is everywhere."

Thank you very much.

Ruth Klotzel

Madrid

24 November 2008

Download this Feature in .

Download this Feature in Spanish.

relatedarticles

03.14.2022 Features

goodbye! and next steps for colleague and friend alexey lazarev

05.27.2020 Features

explorations in ethical design: meditations on equality

05.16.2017 Features

RCA launches new programme: MA Digital Direction

12.14.2016 Features

Interview | Ermolaev Bureau (Moscow)

05.11.2016 Features