RETOOLING IDENTITY PRODUCTION IN THE 21ST CENTURY

01.07.2009 Features

Evert Ypma

Despite design agencies' claim to be visual experts on identity and representational questions, contemporary realities such as cultural diversity and hybrid identities in multicultural social contexts seem to be neglected issues within the profession of identity construction and the production of representation (visual identity design, corporate design and branding).

Even though the overtly expressed search for orientation and identity by individuals, organisations and entire communities cannot be overlooked, designers and identity strategists hardly engage with the unanswered questions sheltered in contemporary hybrid society and markets. Most identity construction and visual identity production remain based on modernistic Eurocentric or neo-liberal Anglo-American methods of identity and representation although social realities have changed over time.

Since the Internet started to be a vital part of consumer daily life we have experienced a worldwide hegemony of branding strategies in professional communication. This superimposed identity plays an enormous role in contemporary society mostly in the form of 'consumable identities' such as product brands, brands of services, political bodies and places, etc. Due to the vast expansion of (online) media possibilities, the production of visual identities to express, manifest and seal artificial identity constructs has increased over the past twenty five years. These constructs have become a new occidentally rooted Esperanto of global culture since they are a cross-cultural, cross-economic, cross-political, cross-religious and cross-geographical phenomenon.

![]()

Above: Nation brand world map. Evert Ypma. 2009.

A lot has been written about branding strategies, mostly summarising the existing discourse in order to make it more effective or efficient. Surprisingly there is not much reflective or critical discourse from within the branding discipline itself. Even when certain brands may be proclaimed success stories, their design strategies and visual identity programmes suffer from an excessive lack of differentiation and repetition of thought, content and form. Similar conceptual lines and comparable processes and techniques are the underlying principles of the current look and feel of the identity industry. Without being seen, it resides in the same delicate virtual area as the recent fall of abstract economics and the dot-com bubble in 2000. Branding is a system of virtual value which did not exist before the nineteen-seventies.

![]()

Above: Differentiation with similar formal and conceptual strategies of present corporate design

![]()

Above: Spread from the Design2context publication 'Dis-Orientation', Lars Müller, 2008

Yet a deeper underlying problem is the widely spread misperception among designers and commissioners that identity seen as a frozen construct, something stable, hermetic and feasible and thus manageable in any form and applicable to any circumstance. This partially can be ascribed to the streamlining influence of design management. Its terms and conditions level out the foundation for plurality and a diversified quality of human visual expression of identity.

Analysing the output of the identity industry, one notices the predominance of corporate managerial efficiency and hierarchy. We also encounter this in the commonly used vocabulary of corporate design practice in which discourses from military organisation, competitive action and the basic assumptions of powers in conflict circulate.

The identity industry does not currently have the right idiom for the deliberate assessment of latent requests from society and markets, for social transformation and cohesion, especially in a context of cultural diversity, or for democratic processes, since current strategies are (with few exceptions) clearly top-down identity design strategies. Brand culture is just one window on reality.

Another aspect that needs to be questioned is that brand culture is based on strategies of exclusivity and a kind of soft power grounded 'inclusiveness' under the condition of loyalty (brand participation). A brand is appealing to individuals because it provides orientation in the social symbolic jungle. Brand identity constructs in the public and private sphere are often described as substitutes for declining cultural story lines. Consumers who flout their exclusiveness by consuming a certain brand can develop an individual sense of belonging to a distinct community (brand tribe), a certain 'common we'. This superficial relationship is accompanied by the monetary transaction. The genetics of branding with its preformatted design formulas is therefore not well suited to answer the questions hybrid society is bringing to the design table.

The contemporary quest for identity must be placed in the light of the various dynamics of the globalisation process at large. In his book Liquid Modernity Zygmunt Bauman states that today, 'we are all on the move'. He points to a world in change, in which boundaries of previous logics, social order and organisation have become fuzzy.[1]

The distinction of traditional bound arise between what used to be clearly separated entities such as government, religion and business is in flux regarding organisational, managerial, financial, cultural and representational aspects. Cities have transformed into dynamic, ever-changing ethnic mosaics of commuters, tourists, (illegal) refugees, migrant workers, governance, business activity, education, friendships and relatives, media flows, and brands. Whereas postwar migration was largely about the flow of postcolonial migrants to their former colonial masters' nations, today migrants are coming from everywhere and generate super-diversity.[2] Their ties with their virtual homeland constitute a kind of 'mediaspora', visible on the Internet, as Valerie Frissen has argued.[3]

If something moves, then other things remains idle.[4] Despite hybridity people still learn that things are divided into stable categories and it is true that these remain partially valid as well. In the social-political landscape there are numerous hostile traditionalist and nostalgic signals which rely upon historic symbolism and meaning. They are often promoted in a commercialised and politicised way and contribute to the contemporary rise of visible identity markers in most societies. In the nineteen-fifties the Hijab (modest dress for Muslim women in public) was less practiced than it is nowadays and the countries of the EU proclaimed unity instead of today's diversity. We see this development also in visual identity production. This process is neither an opposite nor natural reaction, but on a meta-level it is a form of cultural reflection in itself.

Hybridity or cultural mixing assumes the existing of pure cultures, but there are no pure cultures. Every culture is the product of a cultural mix. Ethnic identity boundaries often coincide with cultural boundaries. These ambiguous grey zones between categories and boundaries are the place to study the interplay between culture and identity. The pressure they are under becomes visible through processes marked by negotiation and re-negotiation, transcendence, transformation and reframing all of which are characteristics similar to design essentials. This is similar to design processes in which various perspectives, sources of inspiration and disciplinary knowledge amalgamate in order to produce new functions, objects, situations and meaning. Design is about transformation from one state to another.

Cultural mixing takes place at the level of identity or symbolism (or both). Nothing new, music history exemplifies the processes of mixing; visual designers and amateurs too have been copying and reshuffling visual codes into new ones. In this respect crossovers and the creolisation of culture sometimes engender the unexpected and lead to promising results in the form of new meaning and values. We must not be afraid to borrow knowledge and experience from sources other than our own and let diffusion occur or even stimulate this.

Nowadays all integration politics clearly voices the obligation to foreigners to adapt to local cultural identities and these policies are designed to stimulate them to assimilate to hosting cultures. Within this ambivalence, identity is put under pressure again. On one hand identity formation is a highly fluid concept, especially in a consumer culture in which one can profile his own identity in any form through the adoption of lifestyles and attributes, yet on the other hand strict identity expectations are projected onto newcomers.

Cultural diversity has been recognised by many scholars as an eminent and valuable long-term social capital asset. This value has not yet been allocated and accredited and the quality and prosperity that lies within needs to be articulated much more clearly by design practices and funded by academic discourses.

The question we face today has to do with the receiving country's cultural absorption abilities and the willingness of both (host and migrant) populations to merge into a new entity that exist as complementary parts. Innovation and creativity is needed from every stakeholder in the social process. This integration is about the true investigation of the unknown other.

![]()

Above: 'Phonehouse Geneva'. Project by students made during the MIX & MATCH workshop by Evert Ypma at the University of the Arts Geneva (HEAD), 2007

If it is not successful, hybrid societies will remain multicultural, an admission that these cultures have not mixed. The challenge for identity design is to facilitate the contravention of present fixed forms of image creation and to design new forms of 'super-symbolism' with which hybrid individuals can identify. This must be seen as stimulation to re-think society (or parts of it), motivation for the cultural expression of whence things originate and the exploration and invention of new meaning and its alternative carriers.

With this in mind, designing visual identities can contribute to the expression of diversity between human beings by accepting cultural differences: we agree to disagree.

Identity design is about establishing trust through image creation and pervasive representation. It is positioned at the base of organised image production. Omnipresent junk identities actually swindle this concept of trust. Instead of in-flight magazine imagery we need a kind of iconography that knows of what it speaks and that lets people be surprised, encourages them to think or lets them be part of a play. As an iconographic multiplicity of meaning this can function as a grand conversation in order to establish new forms of trust in participative symbolism again. On this basis new traditions can be proposed and progress over time.

As discussed above, visual identity is already widely employed in bonding processes of individuals and groups to certain goals. But what if we change the directions of effort in order to bridge social hesitation and communication gaps between disconnected individuals in our societies? Identity production can be fostered by experiments and by proposing new visionary statements and languages in the public sphere of communication and design.

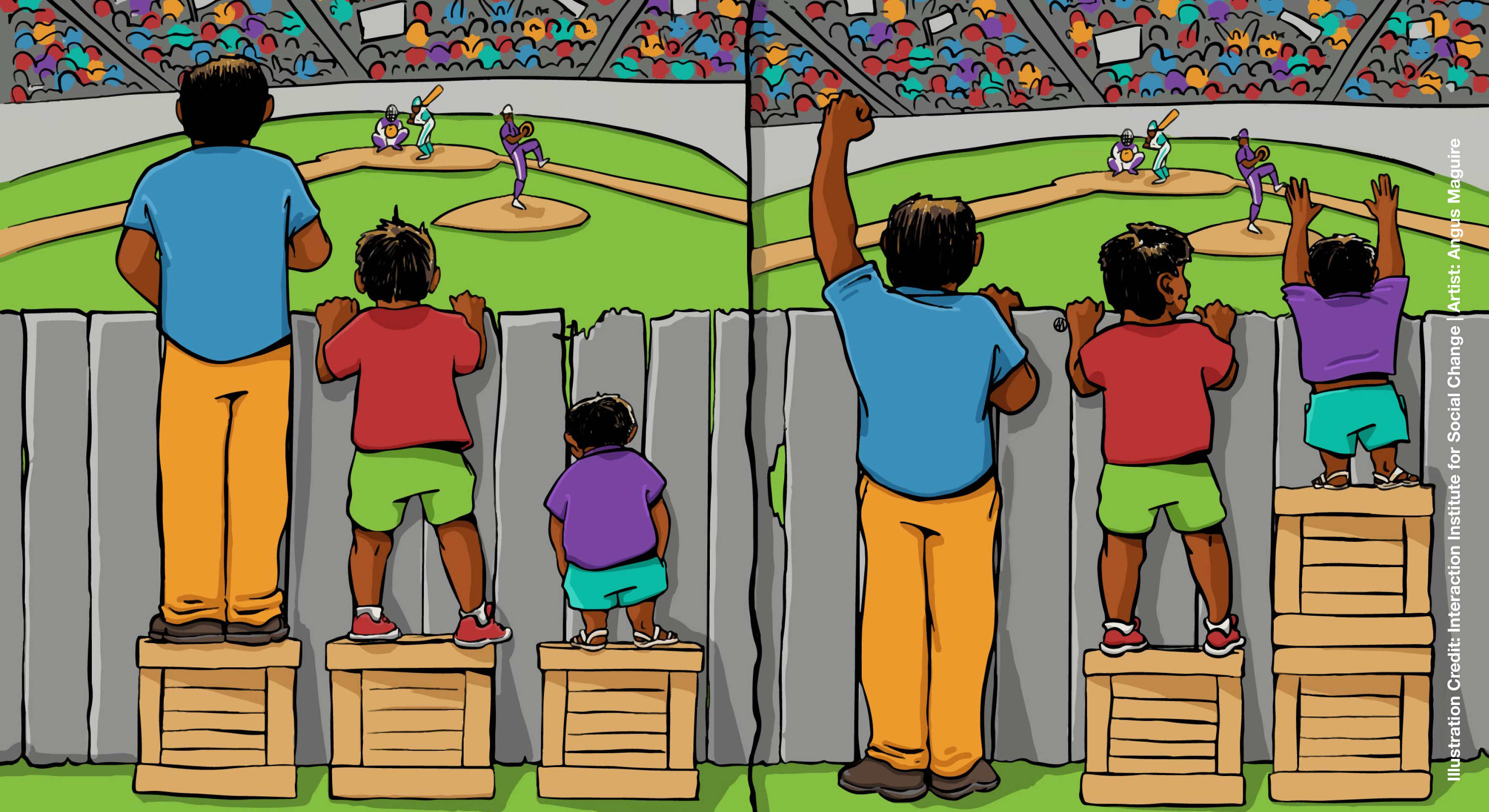

Yet we need to be aware of the externalities and collateral effects of design developments. The 2005 French banlieux riots signaled once more that urban design, government policy, identity politics and dynamics of the market (such as labor) are unmistakably interrelated with identity perception of individuals who suffer from unequal powers of definition. Bottom-up scenarios of identity and identity production deserve to be developed more. This only can happen when we leave our screens and engage ourselves with realities outside.

In other words, our focus should not be on the world of design but about the design of the world, as Bruce Mau once posed. Designers need to develop social antennae. They need to search for problem areas and action fields in which they can introduce their clients as engaged stakeholders.

By recognising current social constraints and acknowledging its urgencies, the agenda for design has been set by committing itself to those real and future identity questions generated by a super-hybridised society. The identity industry should look for the true needs of that new type of society by intensifying reality checks, something which can be done through research into the symbolic orders of social hybridity.

This means that the past and present visual, textual, verbal and spatial strategies of representation, design and communication used in hybrid cultures must be scrutinised not on the formal level only, but on a fundamental level. Research and reflection become an integrated part of practice and instead of affirmations of pre-formulated representations they explore in-depth forms of presence and iconographic engagement with diasporic citizens.

Leaving the narrow lens of branding and releasing itself from the fixed idea of static identity by unraveling the construction of identity more deeply will immediately opens up new types of questions and other associations to identification processes and representation. Design has the ability to stimulate dialectic identity processes or multiple routes of identification at the level of function, norm and emotion in the sense of, 'I am many!' and 'the other is many too!' This multiplicity of identity construction facilitates the discovery of new idioms for identity production. It promises a new diversity of dissimilar forms of visual identity and shared narratives.

It would be good to use the current qualities of design practice, such as affirmation, focus, action and duration, to reach the targets proposed above. Let's be efficient in another diverging direction. We must retool the identity industry for the 21st century, a century in which symbolism is neither enmeshed in cultural entanglements nor is meaninglessly generic. It must become a value creating industry for cultural bridging and social cohesion as well as a creator of anchors for orientation, trust and social-economic prosperity.

Works cited

Evert Ypma, ©2009

This article was originally published in Volume #19 (Spring 2009), an independent quarterly magazine that sets the agenda for architecture and design. The article has been republished with permission of the author.

![]()

About the author

Evert Ypma is designer, strategist and researcher at the Zurich University of the Arts, where he initiated Multiplicity & Visual Identities, a postgraduate design programme on identity and representational questions. He studied graphic design at the Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam (NL), a MA at Post-St.Joost in Breda (NL) and design management at the University of Applied Sciences Northwestern Switzerland.

Evert Ypma

Head postgraduate studies Corporate Design and Visual Identities

Zurich University of the Arts

Design2Context, Institute for Design Research

Hafnerstrasse 39, P.O. Box CH-8031

Zurich

Switzerland

T: +41 43 44 66 206

E:

W: http://multiplicity.zhdk.ch

Despite design agencies' claim to be visual experts on identity and representational questions, contemporary realities such as cultural diversity and hybrid identities in multicultural social contexts seem to be neglected issues within the profession of identity construction and the production of representation (visual identity design, corporate design and branding).

Even though the overtly expressed search for orientation and identity by individuals, organisations and entire communities cannot be overlooked, designers and identity strategists hardly engage with the unanswered questions sheltered in contemporary hybrid society and markets. Most identity construction and visual identity production remain based on modernistic Eurocentric or neo-liberal Anglo-American methods of identity and representation although social realities have changed over time.

Since the Internet started to be a vital part of consumer daily life we have experienced a worldwide hegemony of branding strategies in professional communication. This superimposed identity plays an enormous role in contemporary society mostly in the form of 'consumable identities' such as product brands, brands of services, political bodies and places, etc. Due to the vast expansion of (online) media possibilities, the production of visual identities to express, manifest and seal artificial identity constructs has increased over the past twenty five years. These constructs have become a new occidentally rooted Esperanto of global culture since they are a cross-cultural, cross-economic, cross-political, cross-religious and cross-geographical phenomenon.

Above: Nation brand world map. Evert Ypma. 2009.

A lot has been written about branding strategies, mostly summarising the existing discourse in order to make it more effective or efficient. Surprisingly there is not much reflective or critical discourse from within the branding discipline itself. Even when certain brands may be proclaimed success stories, their design strategies and visual identity programmes suffer from an excessive lack of differentiation and repetition of thought, content and form. Similar conceptual lines and comparable processes and techniques are the underlying principles of the current look and feel of the identity industry. Without being seen, it resides in the same delicate virtual area as the recent fall of abstract economics and the dot-com bubble in 2000. Branding is a system of virtual value which did not exist before the nineteen-seventies.

Above: Differentiation with similar formal and conceptual strategies of present corporate design

Above: Spread from the Design2context publication 'Dis-Orientation', Lars Müller, 2008

Yet a deeper underlying problem is the widely spread misperception among designers and commissioners that identity seen as a frozen construct, something stable, hermetic and feasible and thus manageable in any form and applicable to any circumstance. This partially can be ascribed to the streamlining influence of design management. Its terms and conditions level out the foundation for plurality and a diversified quality of human visual expression of identity.

Analysing the output of the identity industry, one notices the predominance of corporate managerial efficiency and hierarchy. We also encounter this in the commonly used vocabulary of corporate design practice in which discourses from military organisation, competitive action and the basic assumptions of powers in conflict circulate.

The identity industry does not currently have the right idiom for the deliberate assessment of latent requests from society and markets, for social transformation and cohesion, especially in a context of cultural diversity, or for democratic processes, since current strategies are (with few exceptions) clearly top-down identity design strategies. Brand culture is just one window on reality.

Another aspect that needs to be questioned is that brand culture is based on strategies of exclusivity and a kind of soft power grounded 'inclusiveness' under the condition of loyalty (brand participation). A brand is appealing to individuals because it provides orientation in the social symbolic jungle. Brand identity constructs in the public and private sphere are often described as substitutes for declining cultural story lines. Consumers who flout their exclusiveness by consuming a certain brand can develop an individual sense of belonging to a distinct community (brand tribe), a certain 'common we'. This superficial relationship is accompanied by the monetary transaction. The genetics of branding with its preformatted design formulas is therefore not well suited to answer the questions hybrid society is bringing to the design table.

The contemporary quest for identity must be placed in the light of the various dynamics of the globalisation process at large. In his book Liquid Modernity Zygmunt Bauman states that today, 'we are all on the move'. He points to a world in change, in which boundaries of previous logics, social order and organisation have become fuzzy.[1]

The distinction of traditional bound arise between what used to be clearly separated entities such as government, religion and business is in flux regarding organisational, managerial, financial, cultural and representational aspects. Cities have transformed into dynamic, ever-changing ethnic mosaics of commuters, tourists, (illegal) refugees, migrant workers, governance, business activity, education, friendships and relatives, media flows, and brands. Whereas postwar migration was largely about the flow of postcolonial migrants to their former colonial masters' nations, today migrants are coming from everywhere and generate super-diversity.[2] Their ties with their virtual homeland constitute a kind of 'mediaspora', visible on the Internet, as Valerie Frissen has argued.[3]

If something moves, then other things remains idle.[4] Despite hybridity people still learn that things are divided into stable categories and it is true that these remain partially valid as well. In the social-political landscape there are numerous hostile traditionalist and nostalgic signals which rely upon historic symbolism and meaning. They are often promoted in a commercialised and politicised way and contribute to the contemporary rise of visible identity markers in most societies. In the nineteen-fifties the Hijab (modest dress for Muslim women in public) was less practiced than it is nowadays and the countries of the EU proclaimed unity instead of today's diversity. We see this development also in visual identity production. This process is neither an opposite nor natural reaction, but on a meta-level it is a form of cultural reflection in itself.

Hybridity or cultural mixing assumes the existing of pure cultures, but there are no pure cultures. Every culture is the product of a cultural mix. Ethnic identity boundaries often coincide with cultural boundaries. These ambiguous grey zones between categories and boundaries are the place to study the interplay between culture and identity. The pressure they are under becomes visible through processes marked by negotiation and re-negotiation, transcendence, transformation and reframing all of which are characteristics similar to design essentials. This is similar to design processes in which various perspectives, sources of inspiration and disciplinary knowledge amalgamate in order to produce new functions, objects, situations and meaning. Design is about transformation from one state to another.

Cultural mixing takes place at the level of identity or symbolism (or both). Nothing new, music history exemplifies the processes of mixing; visual designers and amateurs too have been copying and reshuffling visual codes into new ones. In this respect crossovers and the creolisation of culture sometimes engender the unexpected and lead to promising results in the form of new meaning and values. We must not be afraid to borrow knowledge and experience from sources other than our own and let diffusion occur or even stimulate this.

Nowadays all integration politics clearly voices the obligation to foreigners to adapt to local cultural identities and these policies are designed to stimulate them to assimilate to hosting cultures. Within this ambivalence, identity is put under pressure again. On one hand identity formation is a highly fluid concept, especially in a consumer culture in which one can profile his own identity in any form through the adoption of lifestyles and attributes, yet on the other hand strict identity expectations are projected onto newcomers.

Cultural diversity has been recognised by many scholars as an eminent and valuable long-term social capital asset. This value has not yet been allocated and accredited and the quality and prosperity that lies within needs to be articulated much more clearly by design practices and funded by academic discourses.

The question we face today has to do with the receiving country's cultural absorption abilities and the willingness of both (host and migrant) populations to merge into a new entity that exist as complementary parts. Innovation and creativity is needed from every stakeholder in the social process. This integration is about the true investigation of the unknown other.

Above: 'Phonehouse Geneva'. Project by students made during the MIX & MATCH workshop by Evert Ypma at the University of the Arts Geneva (HEAD), 2007

If it is not successful, hybrid societies will remain multicultural, an admission that these cultures have not mixed. The challenge for identity design is to facilitate the contravention of present fixed forms of image creation and to design new forms of 'super-symbolism' with which hybrid individuals can identify. This must be seen as stimulation to re-think society (or parts of it), motivation for the cultural expression of whence things originate and the exploration and invention of new meaning and its alternative carriers.

With this in mind, designing visual identities can contribute to the expression of diversity between human beings by accepting cultural differences: we agree to disagree.

Identity design is about establishing trust through image creation and pervasive representation. It is positioned at the base of organised image production. Omnipresent junk identities actually swindle this concept of trust. Instead of in-flight magazine imagery we need a kind of iconography that knows of what it speaks and that lets people be surprised, encourages them to think or lets them be part of a play. As an iconographic multiplicity of meaning this can function as a grand conversation in order to establish new forms of trust in participative symbolism again. On this basis new traditions can be proposed and progress over time.

As discussed above, visual identity is already widely employed in bonding processes of individuals and groups to certain goals. But what if we change the directions of effort in order to bridge social hesitation and communication gaps between disconnected individuals in our societies? Identity production can be fostered by experiments and by proposing new visionary statements and languages in the public sphere of communication and design.

Yet we need to be aware of the externalities and collateral effects of design developments. The 2005 French banlieux riots signaled once more that urban design, government policy, identity politics and dynamics of the market (such as labor) are unmistakably interrelated with identity perception of individuals who suffer from unequal powers of definition. Bottom-up scenarios of identity and identity production deserve to be developed more. This only can happen when we leave our screens and engage ourselves with realities outside.

In other words, our focus should not be on the world of design but about the design of the world, as Bruce Mau once posed. Designers need to develop social antennae. They need to search for problem areas and action fields in which they can introduce their clients as engaged stakeholders.

By recognising current social constraints and acknowledging its urgencies, the agenda for design has been set by committing itself to those real and future identity questions generated by a super-hybridised society. The identity industry should look for the true needs of that new type of society by intensifying reality checks, something which can be done through research into the symbolic orders of social hybridity.

This means that the past and present visual, textual, verbal and spatial strategies of representation, design and communication used in hybrid cultures must be scrutinised not on the formal level only, but on a fundamental level. Research and reflection become an integrated part of practice and instead of affirmations of pre-formulated representations they explore in-depth forms of presence and iconographic engagement with diasporic citizens.

Leaving the narrow lens of branding and releasing itself from the fixed idea of static identity by unraveling the construction of identity more deeply will immediately opens up new types of questions and other associations to identification processes and representation. Design has the ability to stimulate dialectic identity processes or multiple routes of identification at the level of function, norm and emotion in the sense of, 'I am many!' and 'the other is many too!' This multiplicity of identity construction facilitates the discovery of new idioms for identity production. It promises a new diversity of dissimilar forms of visual identity and shared narratives.

It would be good to use the current qualities of design practice, such as affirmation, focus, action and duration, to reach the targets proposed above. Let's be efficient in another diverging direction. We must retool the identity industry for the 21st century, a century in which symbolism is neither enmeshed in cultural entanglements nor is meaninglessly generic. It must become a value creating industry for cultural bridging and social cohesion as well as a creator of anchors for orientation, trust and social-economic prosperity.

Works cited

- Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Modernity (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000).

- Thomas Hylland Eriksen, Globalization, The Key Concepts (Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2007).

- Valerie Frissen in a lecture given within the Multiplicity & Visual Identities program, Amsterdam, 2008.

- Anthony Giddens, Modernity and Self-Identity. Self & Society in the Late Modern Age. (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1991).

Evert Ypma, ©2009

This article was originally published in Volume #19 (Spring 2009), an independent quarterly magazine that sets the agenda for architecture and design. The article has been republished with permission of the author.

About the author

Evert Ypma is designer, strategist and researcher at the Zurich University of the Arts, where he initiated Multiplicity & Visual Identities, a postgraduate design programme on identity and representational questions. He studied graphic design at the Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam (NL), a MA at Post-St.Joost in Breda (NL) and design management at the University of Applied Sciences Northwestern Switzerland.

Evert Ypma

Head postgraduate studies Corporate Design and Visual Identities

Zurich University of the Arts

Design2Context, Institute for Design Research

Hafnerstrasse 39, P.O. Box CH-8031

Zurich

Switzerland

T: +41 43 44 66 206

E:

W: http://multiplicity.zhdk.ch

relatedarticles

03.14.2022 Features

goodbye! and next steps for colleague and friend alexey lazarev

05.27.2020 Features

explorations in ethical design: meditations on equality

05.16.2017 Features

RCA launches new programme: MA Digital Direction

12.14.2016 Features

Interview | Ermolaev Bureau (Moscow)

05.11.2016 Features