explorations in ethical design: meditations on equality

27.05.2020 Features

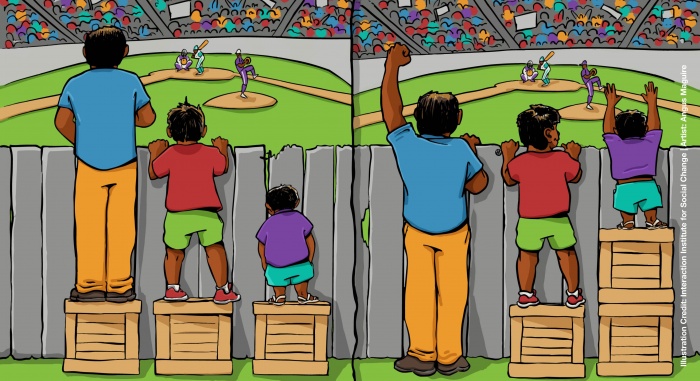

From Interaction Institute for Social Change | Artist: Angus Maguire.

Based on our reflections during the process of reviewing our Best Practice document Model Code of Professional Conduct for Designers, our 'meditation' series positions the role of design in relation to issues of sustainability, diversity and equality. This article is the third in a series; see and Meditations on Diversity. The goal of Mediations on Equality is to inspire your own reflections as designers or design organisations facing issues of inequality—to consider the possibilities for taking a leading role in understanding situated difference and changing the current systems in place—in favour of equality for all. In this reflection, we explore with you the questions:

How can designers design for equality? In what ways can designing be more thoughtful, to address systemic injustice in responsible ways?

We believe that designers have a professional obligation to address inequity in their work; that their work should not create inequality and in fact should — even if it is in some small way— reduce the impacts of existing systemic inequalities on their users.

WHAT ARE WE TALKING ABOUT?

We thought it was important to start any thinking on equality by understanding some of the fundamentals that underpin the principle of equality.

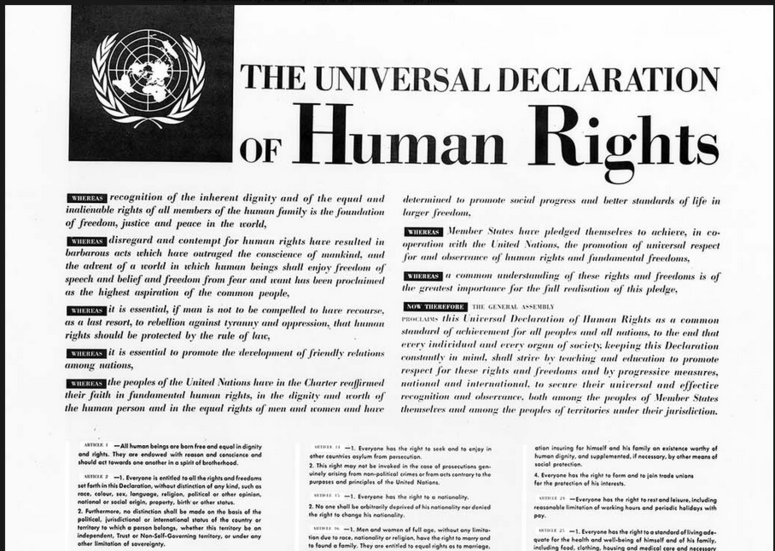

Human rights

Globally, fundamental inequalities exist. The UN Charter of Human Rightsis a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations and outlines 30 Articles to strive for to achieve equality on a universal level.

The UN Charter of Human Rights

Personal freedoms

All citizens have the right to freedom of conscience, freedom of press, freedom of religion, freedom of expression, freedom of assembly, the right to security and liberty, freedom of speech, the right to privacy, the right to equal treatment under the law and due process, the right to a fair trial, and the right to life. 'Civil liberties' as determined by governments, guarantee to their citizens the right to practice their religions, customs and cultural practices. Though civil liberties refer specifically to the rights that governments confer to their citizens, in this day and age, citizen’s personal freedoms are often infringed upon not only by governments, but by private companies.

Read more here:

- Civil Liberties, Wikipedia

- UN Charter of Human Rights, Amnesty International

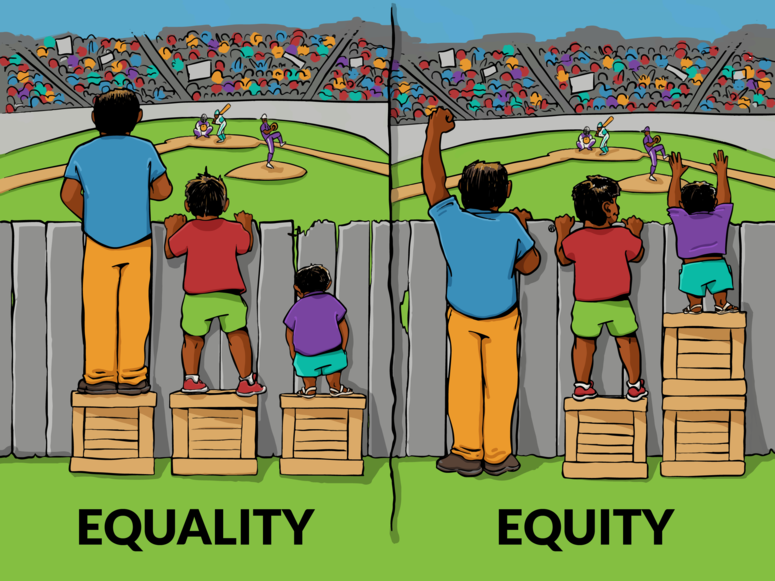

The relationship between “equality” and “equity”

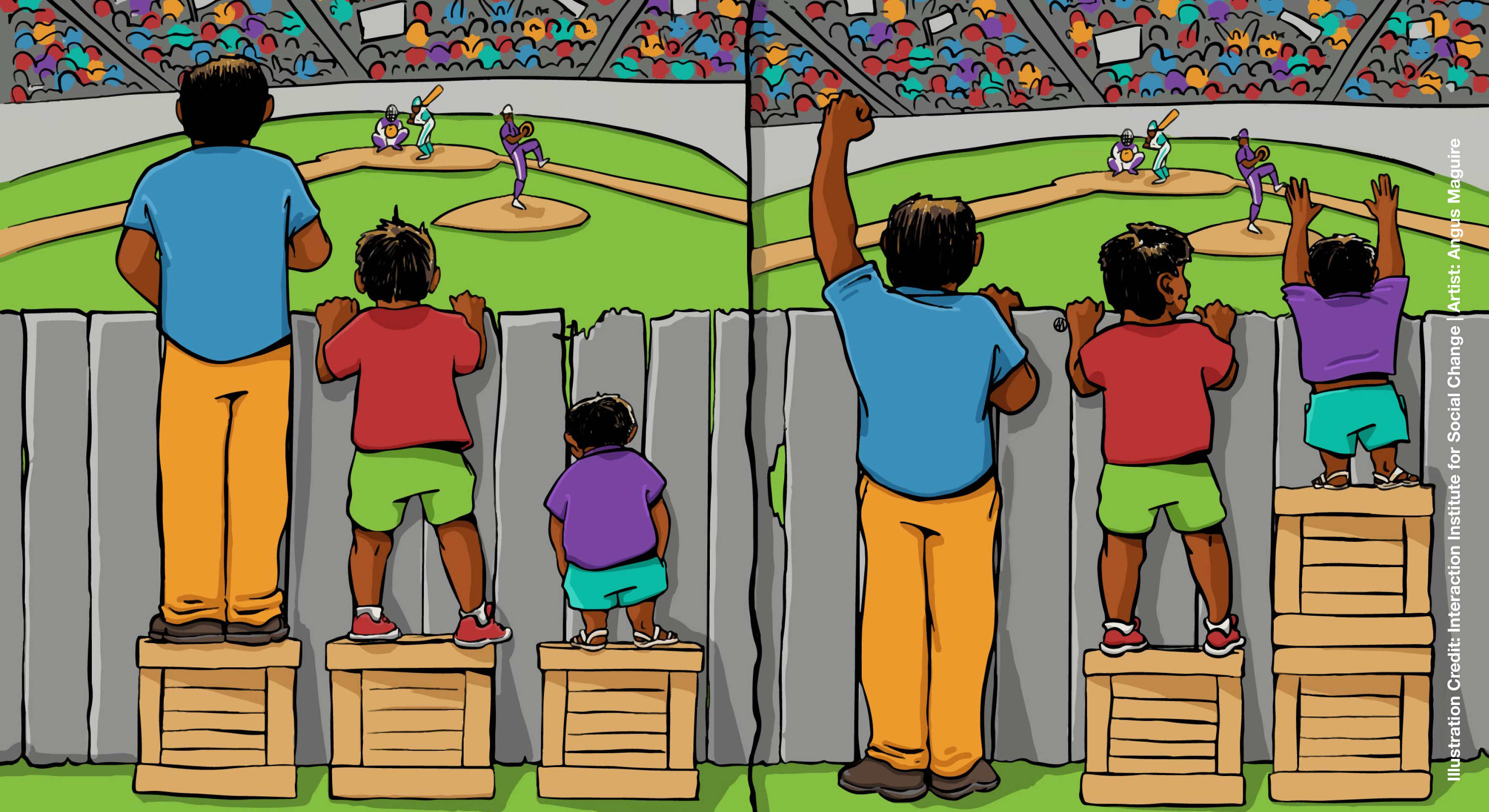

“In the context of societal systems, equality and equity refer to similar but slightly different concepts. Equality generally refers to equal opportunity and the same levels of support for all segments of society. Equity goes a step further and refers offering varying levels of support depending upon need to achieve greater fairness of outcomes.”

Read more here:

- Equality Vs. Equity, Diffen

WHY SHOULD DESIGNERS CARE ABOUT EQUALITY?

The Montréal Design Declaration states that it is the fundamental and critical role of design to create a world that is “environmentally sustainable, economically viable, socially equitable, and culturally diverse”. This is very connected to the idea that the designer — as a professional — has a responsibility to the society they live in. The designer does not design in a void, they cannot simply consider the wishes of the client and some sub-group of potential users. The designer is professionally bound to balance the individual rights and benefits of individuals versus the rights and benefits of society and that includes marginalised groups. Systems of inequality and inequity are often invisible and their power structures dispersed, so that injustice cannot be easily pinned down to one person, place or thing. This adds complexity to the role of the designer in addressing this context.

The currency of inequality and inequity can be social, economic or environmental:

— social: granting rights, social connections, part of in-group (or excluding from)

— economic: access to economic resources

— environmental: access to nature, clean water, unsoiled earth

DESIGNING FOR EQUALITY

“Design is a discipline deeply entangled in the dynamics of inequality. It enacts and enforces them; it is both a producer of these mechanisms, and is informed by them.” (Ece Canlı and Luiza Prado de O. Martins, Design and Intersectionality: Material Production of Gender, Race, Class–and Beyond)

The designer is a gatekeeper. Everything a designer does either supports or opposes the current status quo. How a designer designs could determine who has access to spaces, information and resources. This means balancing the individual rights and the benefit of individuals versus the rights and benefits of the group.

Lately we’ve been hearing a lot about de-centering design away from dominant narratives and canons, methods and practices, in order to give more space and prominent voice to women designers, designers of colour, designers of all ages and from different classes, shifting our focus to other communities in order to achieve 'diversity' and 'inclusion;. Historical precedents (colonialism for instance) have shown us how dominant, Eurocentric models (in design and otherwise) have shaped how we see the world and behave within in it.

While designing for inclusivity is a practical consideration within the design process addressing who you are designing for, designing for equality is a political consideration, entailing a conscious effort to redress the context you are designing in. When we design with equality in mind, we consider not only the diversity of people present, but we try to understand the systems and environments in which these people live, and why aspects of these systems do not make things fair for all. The complexity of the world right now — due to webs of interrelated systems (economic, environmental, social) can make each decision a designer makes a high stakes game. Designers are not lawyers or ethicists, and there are so many variables to consider with each new project or problem. Using design to rectify systemic inequalities might mean establishing professional codes of conduct, values and ethics that are inclusive of a wide spectrum of people that can be applied locally and be instituted at a policy level by governments across a range of countries and contexts.

The Council firmly believes that designers are professionals. And as professionals, we have a responsibility that goes beyond that of the individual clients and users you are working with. As professionals entrusted with decisions that impact the public good, we have a responsibility to society at large and to the members of that society that are marginalised or excluded. We believe that designers have a professional obligation to address inequality in their work. That their work should not create inequality and in fact should — even if it is in some small way — reduce the impact of existing systemic inequalities on their users.

HOSTILE DESIGN: WHEN DESIGN GOES WRONG

One of designers’ areas of expertise is the understanding of human behaviour. We use this knowledge to guide users to better understand our designs. Designers understand that they can direct users through visual cues. They can guide through a space with adequate way-finding, lead users through the functioning of an object by placement, size, form (think of the “home” button on your phone), that they can make information more clear by adjusting font size and placement, etc. But this knowledge can be used against the 'user'. 'Hostile designs' are designs that purposefully work against people. They are made specifically to exclude, harm or otherwise hinder the freedom of a human being.

Twitter post from @ethicalpioneer (social entrepreneur based in Northampton, England)

Hostile design can, for instance, target people who use or rely on public space more than others, such as youth and the homeless, by restricting the physical behaviours in which they can engage, by using the design of outdoor furniture to exclude their uses. Examples of this phenomenon abound in urban furniture design (airport benches designed to preclude stranded travellers from sleeping comfortably, anti-homeless floor studs, benches designed to stop skateboarders, etc.).

Read more about hostile design:

- Hostile Architecture, Wikipedia

- The Two Faces of the Smart City, Fast Company

- Design's exclusion problem, The Extra Crunch

- How Cities Use Design to Drive Homeless People Away, The Atlantic

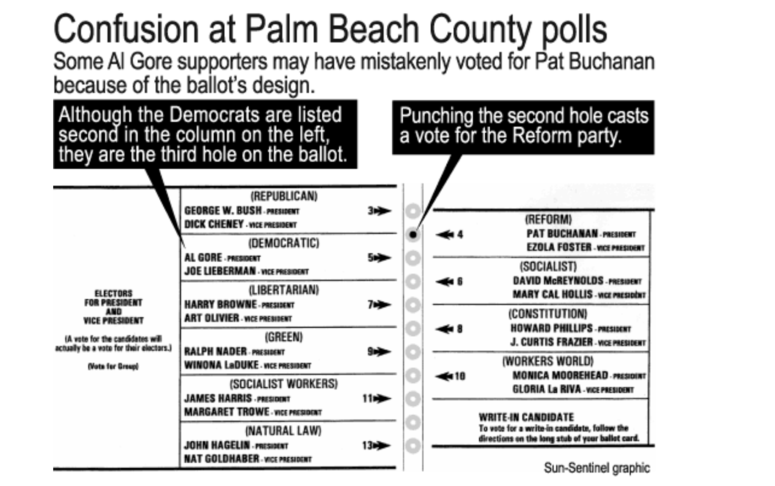

Through big data, design might exclude certain types of people from seeing a message, or use design to manipulate political outcomes. Examples of this run from the annoying (accidentally subscribing to email spam) to the outright devious (Facebook, Cambridge Analytica and the manipulation of millions using targeted ads.) Even something as seemingly mundane as the graphic design of voting ballots can manipulate the outcome of an election. In an article about ballot design and its consequences published in the journal Electoral Studies authors Andrew Reynolds and Marco Steenbergen come to the conclusion that “the negative correlation between ballot design and spoilt ballots, combined with the weight of historical evidence which shows that ballots are often a highly manipulative tools of political symbolism, implies that ballot papers symbols, photographs, layout, and color are of most interest as political cues (for both literate and illiterate voters).”

Read more here:

- Facebook’s New Controversy Shows How Easily Online Political Ads Can Manipulate You, TIME

- How the world votes: The political consequences of ballot design, innovation and manipulation, Electoral Studies

From How important is Ballot Design? , ethics in graphic design

THE GLOBAL SOUTH, THE “THIRD WORLD” AND COLONISATION

In his piece Decolonising Design Ahmed Ansari, Director of the PhD program in Technology, Culture and Society at NYU, asks “What could non Anglo-European accounts of history, and history read differently, both from the grassroots experiences of people invisible to history to the macro-historical readings of changes across centuries and millennia, do to inform design history? What could design theory learn from the knowledge systems of non Anglo-European cultures throughout history that thought and theorized about design, creativity, practice, craft, technology etc. differently?” This is the center of the argument for the “decolonisation” of design.

“Decolonizing is about unearthing, shifting the glance, de-centering, giving agency, being vulnerable, making mistakes, ideation, thinking about our communities, and not so much design.”— Ramon Tejada, professor at the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence

In a series of articles posted on the AIGA blog “Eye on Design” designer Anoushka Khandwala attempts to dismantle the norms we accept around design history and some ingrained design methodologies we might be unconsciously working with. She explores ideas of decolonising design labor (i.e. the makeup of the design workforce, which is still skewed to the white, male and European), differentiating the term from diversity, and deconstructing the Eurocentric historical design canon.

In the Decolonising Design Manifesto, published in the Journal of Futures Studies, a collective of design scholars, including Ansari state that the discussion about decolonisation needs to move beyond the academic into practice:

"We believe that a sharper lens needs to be brought to bear on non-western ways of thinking and being, and on the way that class, gender, race, etc,. issues are designed today. We understand the highlighting of these issues through practices and acts of design, and the (re)design of institutions, design practices and design studies (efforts that always occur under conditions of contested political interests) to be a pivotal challenge in the process of decolonisation. We also want to move beyond academic discourse to critique and think around the ideas and practices that circulate through the work of professional designers embedded in the various sectors of production that stimulate and sustain the modern/colonial world economy."

The discussion on decolonisation stems from the idea that as long as designers are not conscious of the weight of history on their assumptions and worldview, their design will exclude — if unwittingly— the ‘rest’ of the world, compounding the existing inequalities.

- Decolonising Design, Ahmed Ansari

- , Journal of Future Studies

- What Does It Mean to Decolonize Design? Dismantling design history 101, Anoushka Khandwala

- Decolonizing Means Many Things To Many People: Four Practitioners Discuss Decolonizing Design, Anoushka Khandwala

·

ADDRESSING INEQUALITY IN DESIGN WITH HUMAN RIGHTS APPROACHES

One area in which the ethical considerations of design have been much publicised is Artificial Intelligence (AI). AI is radically changing society by translating languages, driving cars, detecting cancer, and other great applications. But AI is also at risk of causing harm: when programming a self-driving car, there are many ethical decisions that need to be made when determining whose life will be spared in an accident for instance. By instilling predictive policing technology such as facial recognition, which can reinforce bias and disproportionately affecting poor communities, women or minorities especially when used for law enforcement.

As we increasingly let algorithms and scripts make decisions that impact the lives and well-being of people and societies, it is becoming paramount to put in place a solid ethical framework to protect them. Caroline Sinders is a designer and researcher at Wikimedia, and a BuzzFeed/Eyebeam Open Lab Fellow, she is specialised in design for machine learning and user research. She has proposed such a framework, the Six principles of Human Rights Centered Design, an approach that is based on protecting personal freedoms, giving the user the tools and the power to make their own decisions, actively defending diversity and taking a cautious approach to innovation:

- Human Rights Centered Design is about privacy and data protection first, recognising that data is human, inherently and always.

- It puts the user’s agency first by always focusing on consent. Always offer a way for a user to say yes or no, without being tricked or nudged.

- It doesn’t design with only opt-out in mind; it puts choice at the forefront of design.

- It designs for the Global South first, and centers diversity of experiences.

- It actively asks “What could go wrong in this product?”—from the benign to the extreme—and then plans for those use cases.

- It views cases of misuse as serious problems and not as edge cases, because a bug is a feature until it’s fixed.

For more on this approach and the thinking behind it:

- We Need a New Approach to Designing for AI, and Human Rights Should Be at the Center, Caroline Sinders

From this example, we can garner certain clues on how to design more equitably:

— Awareness: investigating the hidden mechanisms that create inequality, identifying solutions, transparency towards and collaboration with users and those affected by the designs

— Transparency: users may appreciate some thoughtful guidance but the design process should be transparent enough to allow for the user to consent

— Discussion and thought development: creating and disseminating a body of knowledge and discourse around design equality

— Engaging stakeholders: clients, colleagues, communities, policy makers, and citizens to create new solutions for achieving equality

FINAL THOUGHTS

Our work at the International Council of Design is about drawing boundaries as well as forging pathways for designers to create solidarity and collective action. To advocate, through their professional and ethical standards, for a systemic shift towards a sustainable economy that is equitable for people and good for the planet. We don’t have all the answers, but by holding diverse forums for global conversations, and by developing codes of professional conduct and ethics that apply to a variety of global contexts—we are striving to create aspirational models for change that individual designers and larger organisations can use as guides.

We firmly believe that design can intervene at a much higher level. Designers have the tools to implement systemic change: Re-thinking production and consumption models, dematerialising processes and impacting social habits. But designers cannot do this alone. Design is a collaborative process. As difficult as we know it is, we need to seek to get out of our comfort zone and engage with the non-design world. Work with governments, businesses, and community organisations to implement and test collaborative solutions.

relatedarticles

goodbye! and next steps for colleague and friend alexey lazarev

RCA launches new programme: MA Digital Direction

Interview | Ermolaev Bureau (Moscow)