The Blank Slate

04.09.2014 Features

Sara Breselor

In this article originally published in Communication Arts September/October 2014 issue, design educators explain that in order to prepare students for the field, they must first determine what, exactly, the designer of the future will do.

Quick quiz: define, in ten words or fewer, the role of the modern designer. Not that easy, is it? There are plenty of designers out there, but it’s become difficult to find a common definition for what it is they do. Technology has distanced design from its roots in craft, ushering out the drafting tools, rubber cement, transfer lettering and T-squares, and with them the notion that a designer’s work is defined by any specific production process. The very idea of “communication design” has been rendered impossibly vague by the sheer number of communication channels available and by the ability to target a message to a global audience or any number of precise subsets within it, right down to the individual level. Further complicating the issue are the democratizing effects of technology: anyone with a computer has all the tools they need to execute graphic, print, web and even interactive designs and distribute them to a virtually limitless online audience.

Terry Irwin, head of Carnegie Mellon School of Design, says, “These changes have thrust design into a period of self-reflection as well as opportunity.” Professionals have been forced to find new ways to distinguish themselves from a flood of armchair designers, but they also have the freedom to redefine their work within the wide-open context of a field whose traditional boundaries have been removed. “Ask a designer what he or she does, and each one will have a different response,” say design educators Steven Heller and Lita Talarico, co-chairs of the MFA design program at the School of Visual Arts in New York. “We are becoming multidisciplinary, extra-disciplinary and hybridized,” they say.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of this period of change is the fact that even as so much of the field has been thrown into question, designers have become increasingly relevant, sought after not so much for what they do as for how they do it. Organizations of all types, from corporations to nonprofits to governments, have fallen in love with “design thinking”—applying design’s problem-solving approach to all kinds of noncommunication design issues.

The question for design educators, then, is how to prepare students to take advantage of the opportunities this presents. How do you teach a discipline in which a way of thinking about problems will be applied to an almost limitless variety of issues? How can you ensure that students have the required skills when those skills have become at once more diverse and less tangible?

![]()

AIGA has been working with Adobe since 2006 on a project called Defining the Designer of 2015, conducting extensive interviews, focus groups, workshops and surveys with educators, employers and observers of the field to determine the skills and qualities that will characterize the successful designer of the near future. A key part of the project was the development of a list of the thirteen most important competencies for the modern designer, and first on the list is the ability to create visual solutions based on an understanding of hierarchy, typography, aesthetics and composition—basic, traditional design skills. But the rest of the list indicates a profound shift in focus toward problem solving, strategy, cultural awareness, ethics, collaboration, management and communication. “As designers have been asked to address more complex problems, the component most often lacking involves the elements of a liberal education that bring context to solutions,” says AIGA executive director Richard Grefé. “Design schools have provided a lean offering of humanities and social sciences in the past; now they must either partner with other institutions or augment their faculty to meet this need.”

As Grefé points out, defining these competencies will help traditional design education programs adapt in order to prepare students for a brave new world. But some of the country’s most forward-thinking design educators say that simply adapting will not suffice. “It’s not enough to add a design-thinking or sustainability course to a curriculum and call it a new program,” says Nathan Shedroff, head of the MBA program in design strategy at California College of the Arts. “Schools need to rethink how they teach everything, including accounting, economics, finance, operations, business law—everything.”

CCA’s design strategy program is one of three design MBA programs at the college, the other two being public policy design and strategic foresight. The programs are not aimed at training students to be designers per se, but to be business leaders who approach their work from a design perspective. “This is about creative leadership, not only in product and service development, but also in operations, HR, IT, finance and marketing,” Shedroff says. “We emphasize design thinking and customer-based innovation, sustainability and systems thinking, and explore business model values other than profit, such as positive social, cultural or ecological impact, in every course.” The programs also empha-size soft skills that may not have been part of a design education a generation ago. “Traditional programs often hope students pick up competencies like communication, collaboration and leadership skills simply through working on group projects, but we actually teach these skills and then critique our students as they employ them on projects and in teams,” Shedroff says. “They learn by doing, as they’re always in project-based learning situations and often working with real organizations as part of their schoolwork.”

![]()

Heller and Talarico of the School of Visual Arts lead an MFA program, not an MBA—a degree in art rather than business—but their focus is multidisciplinary, entrepreneurial and aimed at extending the designer’s capabilities with a range of business skills. “Designers are business people: some of us provide services, and others of us invent things,” they say. “To survive in an increasingly competitive field we must present well, negotiate well and work well on various platforms. If you want to put a viable product into the market, you have to know how much it will cost, where you will sell it and what your return might be.” To incorporate these skills into design education, Heller and Talarico make sure that all student work is hands-on and that students are provided with constant exposure to experts in the field who are successfully negotiating entrepreneurial projects.

Irwin has been working for more than four years to reinvent the graduate programs at Carnegie Mellon School of Design in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, with an eye less toward business specifically and more toward creating sustainability in society and the natural world. “Powerful technologies have forced a new kind of design education to emerge that is less about form-giving and more about understanding the dynamics at work in social systems,” she says. The new graduate programs, which will be implemented this fall, are all structured within the theme of “design for interactions,” which means designing to shape the behavior not only of people, but also of the services they use and the larger systems in which they live. The user-centered approach is situated in, and informed by, ethics and awareness of social and environmental concerns. “Design has been incredibly self-referential,” Irwin says, so the new programs will require students to do a lot of reading outside the field and to learn to work on teams with people from other disciplines in order to solve problems. “You need to be able to let your jargon go and communicate,” she says. “You need to work with the absolute conviction that what the ten of you can create together is better than anything you could create on your own.”

![]()

Irwin’s vision is for the designer of the future to be an agent of positive change, creating innovative, sustainable human systems and lifestyles. “We have a dearth of meaning,” she says. “If design is about looking cool and winning awards, it’s going to be a hollow enterprise.” She shares with Grefé, Shedroff, Heller and Talarico a desire to foster leaders who will use design to make an impact on the world far beyond the scope of what traditionally would have been understood as the design profession. This rethinking of design’s role in business and society “is really about reemphasizing the qualitative—skills, research, processes, perspectives, priorities—alongside the quantitative,” says Shedroff. “Numbers and metrics drive too many institutional decisions, and it’s created a world in which the most important qualities of life are dwindling in the name of efficiency.” These forward-thinking educators see the potential for design’s unique problem-solving tactics to tangibly improve the world we live in, which, Grefé notes, is ultimately good for the profession. “Design involves a kind of integrative thinking that is supported by empathy, creativity and execution,” he says. “In moving from solving the problem of communicating to solving other problems affecting the human experience, design has become more relevant to society, and thus it has become more valuable.”

Reprinted with permission by Sara Breselor, All rights reserved.

This article first appeared the September/October 2014 issue of Communication Arts Communication Arts. Read original Article here

![]()

Sara Breselor (sarabreselor.wordpress.com) is a San Francisco–based writer and the editor of the IDEO Labs website. She’s a regular contributor to Wired and the Harper’s Weekly Review, and her writing has also appeared in Idiom magazine, Salon and Slate.

In this article originally published in Communication Arts September/October 2014 issue, design educators explain that in order to prepare students for the field, they must first determine what, exactly, the designer of the future will do.

Quick quiz: define, in ten words or fewer, the role of the modern designer. Not that easy, is it? There are plenty of designers out there, but it’s become difficult to find a common definition for what it is they do. Technology has distanced design from its roots in craft, ushering out the drafting tools, rubber cement, transfer lettering and T-squares, and with them the notion that a designer’s work is defined by any specific production process. The very idea of “communication design” has been rendered impossibly vague by the sheer number of communication channels available and by the ability to target a message to a global audience or any number of precise subsets within it, right down to the individual level. Further complicating the issue are the democratizing effects of technology: anyone with a computer has all the tools they need to execute graphic, print, web and even interactive designs and distribute them to a virtually limitless online audience.

Terry Irwin, head of Carnegie Mellon School of Design, says, “These changes have thrust design into a period of self-reflection as well as opportunity.” Professionals have been forced to find new ways to distinguish themselves from a flood of armchair designers, but they also have the freedom to redefine their work within the wide-open context of a field whose traditional boundaries have been removed. “Ask a designer what he or she does, and each one will have a different response,” say design educators Steven Heller and Lita Talarico, co-chairs of the MFA design program at the School of Visual Arts in New York. “We are becoming multidisciplinary, extra-disciplinary and hybridized,” they say.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of this period of change is the fact that even as so much of the field has been thrown into question, designers have become increasingly relevant, sought after not so much for what they do as for how they do it. Organizations of all types, from corporations to nonprofits to governments, have fallen in love with “design thinking”—applying design’s problem-solving approach to all kinds of noncommunication design issues.

The question for design educators, then, is how to prepare students to take advantage of the opportunities this presents. How do you teach a discipline in which a way of thinking about problems will be applied to an almost limitless variety of issues? How can you ensure that students have the required skills when those skills have become at once more diverse and less tangible?

AIGA has been working with Adobe since 2006 on a project called Defining the Designer of 2015, conducting extensive interviews, focus groups, workshops and surveys with educators, employers and observers of the field to determine the skills and qualities that will characterize the successful designer of the near future. A key part of the project was the development of a list of the thirteen most important competencies for the modern designer, and first on the list is the ability to create visual solutions based on an understanding of hierarchy, typography, aesthetics and composition—basic, traditional design skills. But the rest of the list indicates a profound shift in focus toward problem solving, strategy, cultural awareness, ethics, collaboration, management and communication. “As designers have been asked to address more complex problems, the component most often lacking involves the elements of a liberal education that bring context to solutions,” says AIGA executive director Richard Grefé. “Design schools have provided a lean offering of humanities and social sciences in the past; now they must either partner with other institutions or augment their faculty to meet this need.”

As Grefé points out, defining these competencies will help traditional design education programs adapt in order to prepare students for a brave new world. But some of the country’s most forward-thinking design educators say that simply adapting will not suffice. “It’s not enough to add a design-thinking or sustainability course to a curriculum and call it a new program,” says Nathan Shedroff, head of the MBA program in design strategy at California College of the Arts. “Schools need to rethink how they teach everything, including accounting, economics, finance, operations, business law—everything.”

CCA’s design strategy program is one of three design MBA programs at the college, the other two being public policy design and strategic foresight. The programs are not aimed at training students to be designers per se, but to be business leaders who approach their work from a design perspective. “This is about creative leadership, not only in product and service development, but also in operations, HR, IT, finance and marketing,” Shedroff says. “We emphasize design thinking and customer-based innovation, sustainability and systems thinking, and explore business model values other than profit, such as positive social, cultural or ecological impact, in every course.” The programs also empha-size soft skills that may not have been part of a design education a generation ago. “Traditional programs often hope students pick up competencies like communication, collaboration and leadership skills simply through working on group projects, but we actually teach these skills and then critique our students as they employ them on projects and in teams,” Shedroff says. “They learn by doing, as they’re always in project-based learning situations and often working with real organizations as part of their schoolwork.”

Heller and Talarico of the School of Visual Arts lead an MFA program, not an MBA—a degree in art rather than business—but their focus is multidisciplinary, entrepreneurial and aimed at extending the designer’s capabilities with a range of business skills. “Designers are business people: some of us provide services, and others of us invent things,” they say. “To survive in an increasingly competitive field we must present well, negotiate well and work well on various platforms. If you want to put a viable product into the market, you have to know how much it will cost, where you will sell it and what your return might be.” To incorporate these skills into design education, Heller and Talarico make sure that all student work is hands-on and that students are provided with constant exposure to experts in the field who are successfully negotiating entrepreneurial projects.

Irwin has been working for more than four years to reinvent the graduate programs at Carnegie Mellon School of Design in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, with an eye less toward business specifically and more toward creating sustainability in society and the natural world. “Powerful technologies have forced a new kind of design education to emerge that is less about form-giving and more about understanding the dynamics at work in social systems,” she says. The new graduate programs, which will be implemented this fall, are all structured within the theme of “design for interactions,” which means designing to shape the behavior not only of people, but also of the services they use and the larger systems in which they live. The user-centered approach is situated in, and informed by, ethics and awareness of social and environmental concerns. “Design has been incredibly self-referential,” Irwin says, so the new programs will require students to do a lot of reading outside the field and to learn to work on teams with people from other disciplines in order to solve problems. “You need to be able to let your jargon go and communicate,” she says. “You need to work with the absolute conviction that what the ten of you can create together is better than anything you could create on your own.”

Irwin’s vision is for the designer of the future to be an agent of positive change, creating innovative, sustainable human systems and lifestyles. “We have a dearth of meaning,” she says. “If design is about looking cool and winning awards, it’s going to be a hollow enterprise.” She shares with Grefé, Shedroff, Heller and Talarico a desire to foster leaders who will use design to make an impact on the world far beyond the scope of what traditionally would have been understood as the design profession. This rethinking of design’s role in business and society “is really about reemphasizing the qualitative—skills, research, processes, perspectives, priorities—alongside the quantitative,” says Shedroff. “Numbers and metrics drive too many institutional decisions, and it’s created a world in which the most important qualities of life are dwindling in the name of efficiency.” These forward-thinking educators see the potential for design’s unique problem-solving tactics to tangibly improve the world we live in, which, Grefé notes, is ultimately good for the profession. “Design involves a kind of integrative thinking that is supported by empathy, creativity and execution,” he says. “In moving from solving the problem of communicating to solving other problems affecting the human experience, design has become more relevant to society, and thus it has become more valuable.”

Reprinted with permission by Sara Breselor, All rights reserved.

This article first appeared the September/October 2014 issue of Communication Arts Communication Arts. Read original Article here

About the author

Sara Breselor (sarabreselor.wordpress.com) is a San Francisco–based writer and the editor of the IDEO Labs website. She’s a regular contributor to Wired and the Harper’s Weekly Review, and her writing has also appeared in Idiom magazine, Salon and Slate.

relatedarticles

03.14.2022 Features

goodbye! and next steps for colleague and friend alexey lazarev

05.27.2020 Features

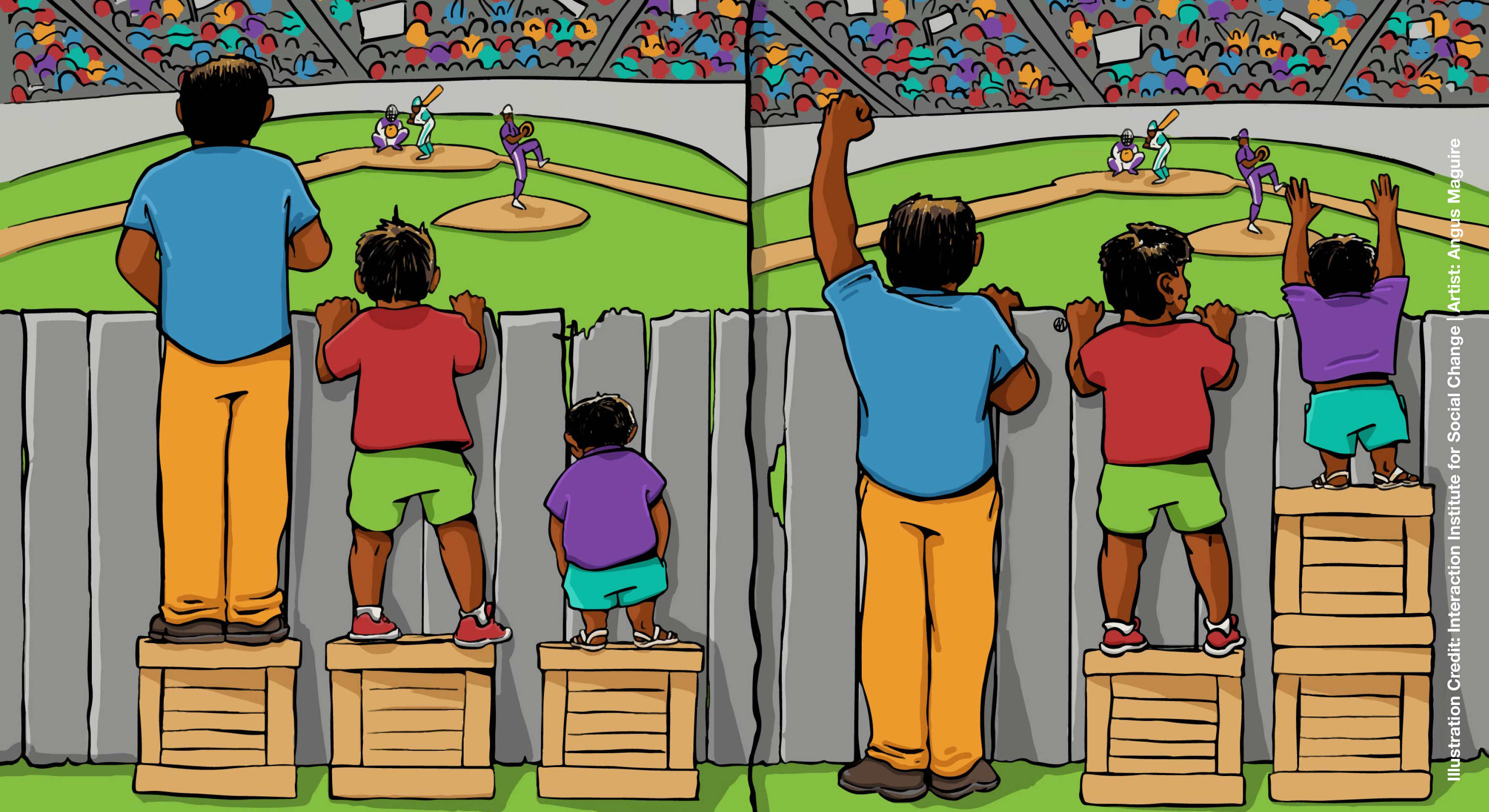

explorations in ethical design: meditations on equality

05.16.2017 Features

RCA launches new programme: MA Digital Direction

12.14.2016 Features

Interview | Ermolaev Bureau (Moscow)

05.11.2016 Features