THE SOUND OF NORTH

18.02.2009 Features

Pat Matson Knapp

While wayfinding tools for the sighted are advancing by leaps and bounds, how does this serve those who are visually impaired? This week's Feature article "The Sound of North", from the recent issue of , looks at the work of David Sweeney, a Royal College of Art researcher using digital technology to provide wayfinding solutions for the visually impaired. From tactile maps to radio-frequency identification (RFID) torches, these new tools can help us "ensure that each and every one of us has total access to all that lies ahead."

New technologies such as RFID tags, Quick Response codes, and Wi-fi routers are dramatically altering wayfinding solutions for the sighted, but digital way finding tools for the visually impaired have been slower to develop.

David Sweeney, a research associate with London's Royal College of Art, is changing all that.

Working in the RCA's Helen Hamlyn Center for people-centered design, Sweeney - an electronics engineer who earned his master's degree in industrial design from RCA - set out to research how new digital technologies could be used to create wayfinding solutions for the visually impaired.

He developed prototypes for three navigation systems that have captured the attention of institutions such as the Victoria & Albert Museum, which has asked Sweeney to pilot them at the V&A.

"The work David is doing is very much in line with our commitment to inclusive design and providing information that is accessible to all," says Karen Livingstone, the V&A's head of projects. "We're very interested in the idea of visitors being able to use their mobile or Blackberry technology to access our exhibitions - and eventually do away with the need for paper."

"Near-future" solutions

Most wayfinding solutions are geared to the needs of people with good eyesight, says Sweeney. "Where systems have been designed for low-vision users, they're generally limited to audio loops that can be expensive to install or Braille, which only a small percentage of people can read."

But the rapid development of wireless technology and the high uptake of personal electronic devices provide new options for the visually impaired. Sweeney has explored how these technologies could be harnessed to enable new forms of navigation that rely less on sight and more on the other senses.

Sweeney's devices use what he calls "near-future" technologies, those that are or soon will be accessible to most people. Using the devices, users access wayfinding information that can be stored on the Internet to provide "blow-by-blow" directions in real time as the user walks through a space.

"People can also post their own directions or comments on a particular space and aid other users," says Sweeney. "And recipients can adjust the amount of information they want to hear."

A key objective in Sweeney's research was to develop concepts that would facilitate the four essential components of wayfinding: orientation, route decision, route monitoring, and destination recognition.

Sweeney tested the devices at the Vassall Centre, a flexible community building in Bristol, England, designed to provide a barrier-free working environment for voluntary organisations oriented to the disabled. (The research was funded by the Audi Design Foundation based on the Vassall Centre's request for wayfinding solutions for its visually impaired users.)

Talking Tactile Map

The Talking Tactile Map combines a physical object with voice information to describe a building using hearing and touch. The shape of the map is a simplified version of the footprint of the actual space. Corridors are indicated by channels, while exits and entrances are indicated by ramps. A large stainless steel ball serves as the "you are here" indicator.

When a user touches the map, he or she hears a spoken description of the function located at that point. The longer the person's finger stays on the spot, the more information they receive. This approach allows the visitor to quickly scan through all the building's functions and services.

At the Vassall Centre, the map is connected to a video screen that displays the information as it's spoken, providing aid to hearing-impaired as well as vision-impaired individuals. User feedback from the testing helped improve the style and depth of the information provided, says Sweeney. The information is stored online, where it can be edited remotely by center staff.

Above: A Google Maps image shows how the talking tactile Map replicates the buildingÂ’s footprint.

Above: David Sweeney's talking tactile Map is a simplified version of the building footprint, with channels indicating corridors and ramps indicating exits and entrances. A stainless steel ball serves as the "you are here" indicator.

RFID Torch

Recognising that tactile maps are static and stationery, and therefore facilitate only the first two wayfinding tasks (orientation and route decision), Sweeney focused on mobile navigation solutions.

The RFID Torch uses RFID (radio-frequency identification) tags as geographic markers. Each tag triggers the torch to speak the information describing that location. When the user lowers the torch and walks away, the description stops.

The markers are interfaces to unlimited quantities of information, accessible whenever the user needs it via a wiki-style website called WikiNav, an online database for location-based information.

The read range of the prototype device is about 15cm, but as RFID technology progresses and Digital Signal Processing systems improve, the range will increase to useful levels, says Sweeney. For Internet access, the torch connects to a mobile phone through a Bluetooth link, but as Near Field Communication technology becomes standard for most mobile phones, an external torch device will soon become unnecessary.

Above: The RFID torch uses RFID tags as geographic markers.

Each tag triggers the torch to speak the information describing that location. The descriptions stop when the user lowers the torch. Image: Courtesy David Sweeney

Smart Camera

The Smart Camera relies on user-owned, camera-equipped mobile phones or MP3 players, along with Internet access.

The system uses Quick Response codes, two-dimensional barcodes that can be read by a mobile phone camera and interpreted into directions. These black and white icons contain digital information that is instantly decoded the moment the camera recognises them. Each icon contains a URL address, which directs the attached mobile phone to retrieve the information stored there. The information is stored digitally and can be communicated in a variety of different ways - visually, aurally, or haptically. During the trials, the Smart Camera communicated it as spoken information.

Above: Smart Cameras are sensitive to QR (Quick Response) codes, two-dimensional data matrices containing digital information that is instantly decoded when the camera recognises them. Each icon contains a URL address, and the URL directs an attached mobile phone to retrieve the information stored there. Image: Courtesy David Sweeney

Toward universal wayfinding

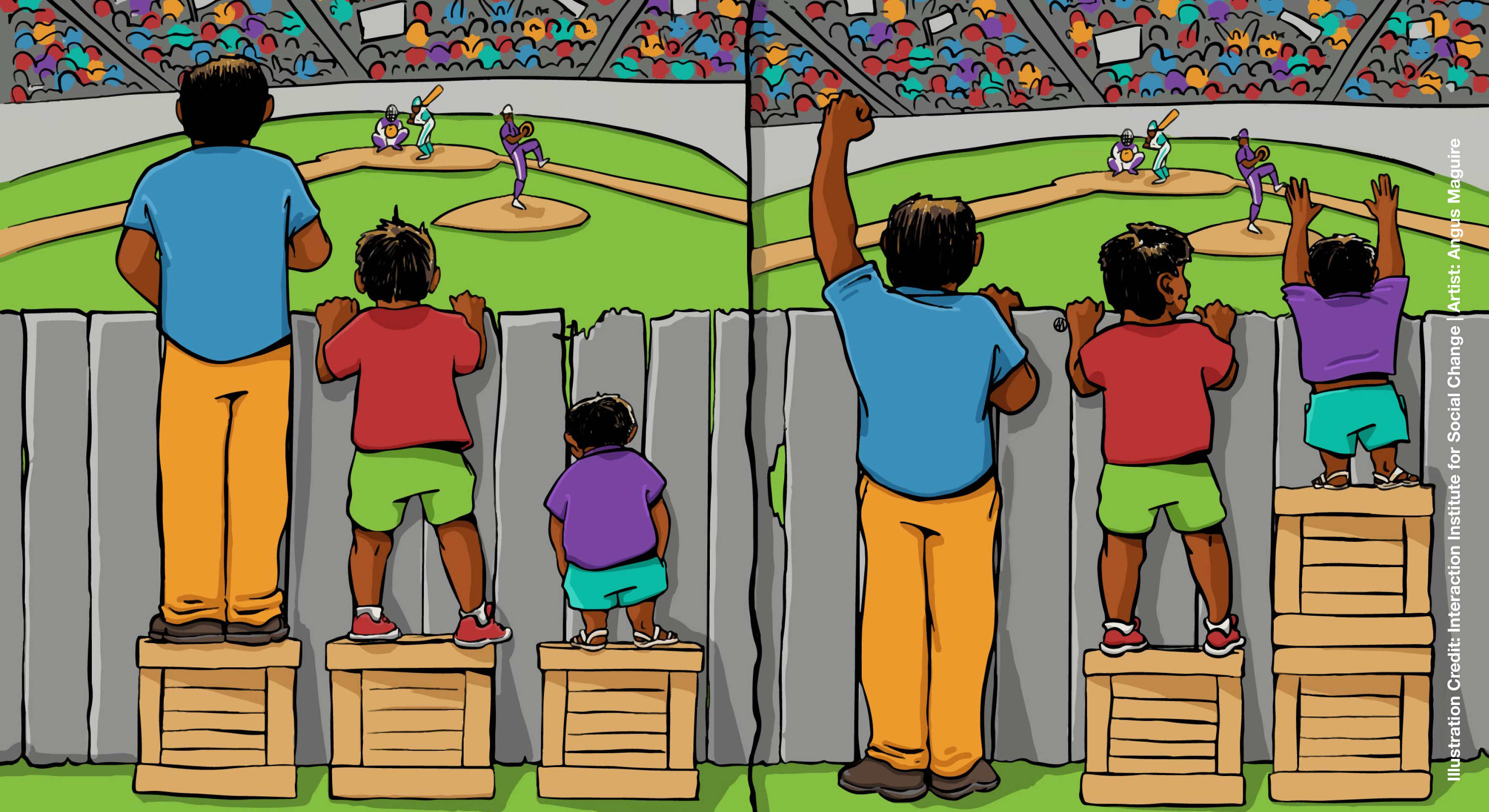

While Sweeney's goal was to improve the experience of the visually impaired user, he also embraced an inclusive design ethos that recognises there would be little benefit in designing a wayfinding system solely for their use.

"Instead of treating those users as a group removed from the wider mainstream, we should treat them as people who have an acute form of something that we all experience - an inability to locate relevant information when we need it."

Digital information has the potential to be accessible to all, Sweeney notes, and the trick is to design interface tools that deliver the information in the ways - and depths - required by different users.

And he says this is the single most important insight to emerge from his research. "We are constantly battling to filter out the important information from the superfluous. Inclusive wayfinding could be expressed in more simple terms, as the barrier-free access of relevant information that is delivered intuitively, on demand, and while mobile."

Essentially, Sweeney notes, wayfinding is just another type of information access. "If we can facilitate an efficient retrieval of information, through sight, sound, or other means, we will not only design improved wayfinding systems, but also improve any other system that involves information transfer, such as museums or other learning environments."

Pathfinder is Sweeney's solution. Pathfinder is an inclusively designed navigation and filtering tool for mobile devices and an online wayfinding community that provides detailed information about locations and services. With a geographic tagging standard in place and the emergence of location-based information sources, Pathfinder is the interface that allows access to information stored on WikiNav and similar sites. With Pathinder, users can customise the types and depth of information they want to received.

Above: Pathfinder is a navigation and filtering tool for mobile devices, a tag product, and an online information community. It allows users to customise the level and types of information they want to receive.

Digitally stored information can potentially be communicated in whichever format a user wishes: onscreen, translated into different languages, spoken aloud, or even conveyed as a series of more exotic stimuli. If users choose to hear this information as spoken text, they can speed it up, slow it down, adjust the emotional range of the speech, change the voice of the person speaking it, etc. It will also incorporate information depth control, which will allow the user to adjust the level and type of information to match his or her needs or experience with the space.

"It's inevitable that information technology will eventually pervade every aspect of our human lives," says Sweeney. "This project emphasises the importance of applying an inclusive design approach while the foundations of this world are being set. We have a responsibility to ensure that each and every one of us has total access to all that lies ahead."

This article originally appeared in segdDESIGN no. 23, 2009, and has been republished with permission.

relatedarticles

03.14.2022 Features

goodbye! and next steps for colleague and friend alexey lazarev

05.27.2020 Features

explorations in ethical design: meditations on equality

05.16.2017 Features

RCA launches new programme: MA Digital Direction

12.14.2016 Features

Interview | Ermolaev Bureau (Moscow)

05.11.2016 Features