Feature | Designing the Australian Style

04.02.2015 Features

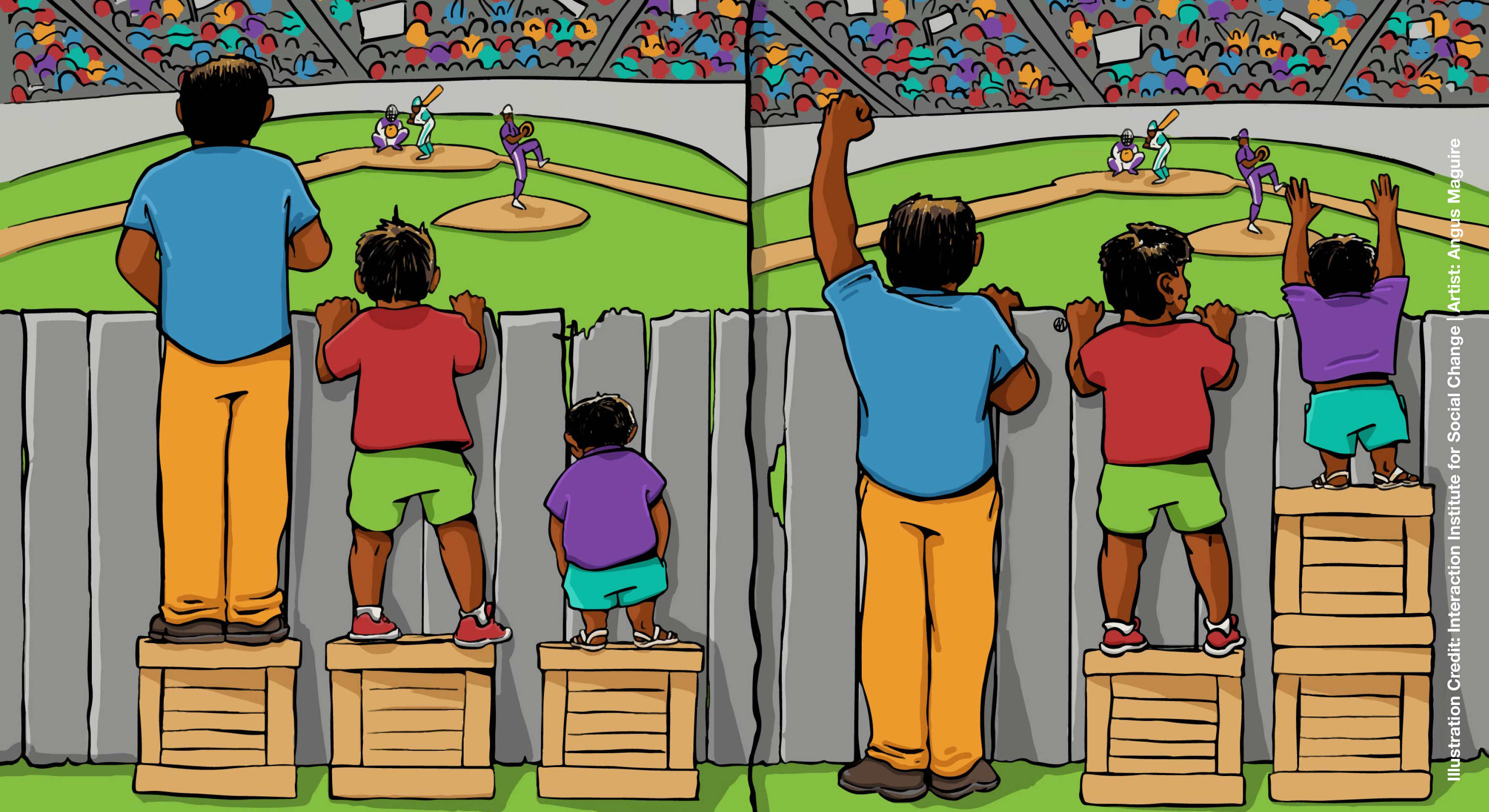

1 The iconic Qantas 747 ‘Wunala Dreaming’ aircraft livery design by DIA Hall Of Fame recipients, John and Ros Moriarty. 2 Detail of Coffee Capsule design For Nespresso Store, Sydney. 3. The ‘Mendoowoorrji’ design for Qantas 737?800 by Balarinji Studio with Paddy Bedford.

(Images courtesy of Qantas and Nespresso)

This feature by ico-D former Past President was first published in the Design Institute of Australia's 'Spark' (Summer 2015) newsletter and is reproduced courtesy of the author and the .

Designing the Australian Style

By Russell Kennedy FDIA

John and Ros Moriarty set the course for authentic representation.

In May 2014, Balarinji founders John Kundereri Moriarty AM and Ros Moriarty were inducted into the Design Institute of Australia’s Hall of Fame. John, a proud Yanyuwa man, is the first indigenous Australian to be bestowed this prestigious honour that formally recognised the pair’s extensive contribution to Australian design.

The Moriartys’ commitment to best practice and promotion of indigenous design knowledge is unparalleled. They have dedicated their lives to indigenous advocacy expressed through an inclusive, accessible and inspired approach to cross cultural communication design.

When interviewed for this article John and Ros spoke passionately about design as a forum to foster deep engagement and understanding between indigenous communities, business, and the broader Australian community. They also clearly articulated the guiding principle to advance the development of an authentic Australian identity. Ros said:

‘We wanted to challenge existing approaches to Australian visual identity which looked largely to Europe and America for inspiration, and which failed, in our view, to harness the unique heartbeat of Australia.’

A different perspective

John described how he formed his view of the Australian identity when he first travelled the world as Australia’s first indigenous national soccer player in the 60s. He found his perspective of home changed when he was living and competing in Europe. ‘I was treated as an equal and people were very interested in knowing about my Aboriginal culture,’ he explained. ‘This was totally different to what I felt at home. It made me feel good and proud of who I was and where I came from. It was the differences not the similarities that interested people. It made me question the attitudes back home and made me think deeply about the Australian identity and its authenticity.

I was an Aboriginal activist at the time – I still am mind you – but my experiences overseas playing soccer enabled me to develop a positive pathway to address some of the issues and concerns I had about Australia and the Australian identity.’

Ros grew up in Tasmania, not having knowingly met an Aboriginal person before beginning a graduate career at the Department of Aboriginal Affairs in Canberra. In her memoir ‘Listening to Country’, Ros describes her childhood immersion in the lakes and mountains of Tasmania as the sense many Australians have about connection to land. It was another layer of belonging that she felt during the trips back to John’s community.

Iconic design work

The Moriartys’ contribution to the broader Australian psyche is backed up by a rich body of work produced over more than thirty years. Their designs have helped many Australians better understand the context of indigenous design knowledge within a broad, multi-faceted national identity. The philosophy of their companies (The Jumbana Group and Balarinji Studio) is ‘Ancient Culture: Contemporary Design’

This mantra is best demonstrated in their seminal design for the Qantas aircraft livery called ‘Wunala Dreaming’. The Boeing 747-400 aircraft was launched in 1994 for a proposed three month promotion, but it was so popular that Qantas kept it flying until 2012, enjoying seventeen years at the forefront of their identity. The Qantas design is a convincing example of how fresh thinking can have a major impact on perceptions and even inspire a paradigm shift in national representation.

Wunala Dreaming marked a pivotal point in cross-cultural design and national representation in Australia. It was a mature, confident, indigenous-led statement. It proudly celebrated Australia’s rich pre-colonial culture as a unique point of difference to the world. It also had a positive impact on other indigenous designers. Alison Page, a Walbanga-Wadi Wadi woman and highly respected spokesperson on design, said: ‘The Balarinji designed Qantas aircraft is a positive example and it’s really visible. I think it is appropriate because Aboriginals designed it. It’s authentic work’.

Uniquely Australian

Fellow DIA Hall of Fame member, Ken Cato commented on the significance of the Balarinji Qantas design in the context of an Australian style: ‘If you’re a designer, the one thing you’re chasing is something different, and yet we ignore thousands of years of history because we feel we’ve got to fit in while at the same time pretending to stand out’. The Qantas design was no accident: Balarinji’s contemporary expression of ancient culture provides clues to creating future expressions of Australian identity. Their design methodology is highly considered and strategically mapped. Their guiding principle is authenticity and they strongly believe that designers need to search from within rather than defaulting to the insecure practice of following other countries.

John and Ros have demonstrated an ability to diplomatically challenge firmly established, post-colonial conventions relating to the representation of Australian identity. By exploring a new relationship between Australia’s indigenous and colonial histories they continue to forge a convergent pathway of cultural hybridity.

Although clearing the path for other indigenous and non-indigenous designers, they caution all practitioners that the journey is not an easy one and that guidance is required. Ros explained that sharing indigenous knowledge requires respectful facilitation within creative and collaborative partnerships. She suggested that cultural education and guidance would provide strategic opportunities for non-indigenous companies. ‘Designers would start to feel that there is a pathway where they can access some of this imagery and knowledge in a good way, and therefore create work that’s more uniquely Australian,’ she said. ‘I believe collaboration is really the mechanism whereby designers can incorporate indigenous imagery into a mainstream market in a way that preserves integrity.’

A new era

Australia is entering a phase in its history that will require us to draw on the experience and knowledge of studios like Balarinji.

Interestingly, ten years after the launch of Wunala Dreaming, the Australian Commonwealth Government finds itself dealing with issues of indigenous recognition and identity at a constitutional level. A national referendum will take place on a date to be determined to formally acknowledge Australia as the home of the world’s oldest continuous living culture.

Constitutional change has the support of both sides of parliament and is expected to receive a ‘yes’ vote. This amendment that will formally acknowledge the pre-colonial occupation of Australia has the potential to change the way Australia views its national identity (past, present and future).

It will raise many issues and designers will be called on to guide us through what will be a significant readjustment of identity, because if we change the way we look at things, then the things we look at will need to change.

Building the way forward

John and Ros make the point that design leaders and professional design associations have an important role to play in guiding their members who operate in the area of indigenous design knowledge and cultural representation.

Leigh Harris, a Kanaluman man and communication designer from Cairns, Queensland, strongly supports the call for greater professional peak body support for indigenous design. ‘I think professional design organisations have a responsibility,’ he says. ‘My personal responsibility is to uphold the challenge of taking indigenous design forward in honour of designers like Clive Atkinson, Marcus Lee and John Moriarty who blazed the trail.’

John and Ros Moriarty’s leadership and guidance demonstrate a course for authentic representation that has worked for Balarinji and The Jumbana Group. It is now up to others to build on their foundations and to advance the broader Australian identity discussion. There is no doubt that there are many more successes ahead, but it must be said that John and Ros will leave an inspiring legacy for Australian designers (indigenous and non-indigenous) who share their quest for authentic representation and a genuine Australian style.

Russell Kennedy is a DIA Fellow, a past President of ico-D, and a Senior Lecturer in Visual Communication Design at Deakin University, Melbourne.

relatedarticles

goodbye! and next steps for colleague and friend alexey lazarev

explorations in ethical design: meditations on equality

RCA launches new programme: MA Digital Direction

Interview | Ermolaev Bureau (Moscow)